We know who Peter Greste is, but does the name Mahmoud Abou Zeid ring a bell?

Al-Habib was, like Foley, a journalist. And, like Foley, he was murdered by Isis. Like Foley, he met his end dressed in a symbolic orange prisoner's jumpsuit, the "star" of a snuff propaganda video. Although in his case he was shot rather than beheaded.

Al-Habib, 21, had been abducted in Raqqa in Syria and accused, alongside fellow media activist Bahsar Abdul Atheem, 20, of photographing oil wells and distributing anti-Sharia leaflets. After confessing on video, the two were tied to a tree and shot in the head.

The murders last week received little attention in the Isis-obsessed British media.

Even the "trial" and "execution" of a woman journalist in Iraq did not cause a stir. Suha Ahmed Radi had been a reporter on a Mosul newspaper until Isis overran the city last year. She then switched to offering stories to news agencies. The move cost her her life. Isis broke into her home, then held her captive for several days before sentencing her to death for espionage and spreading false propaganda.

The Iraqi Journalists Syndicate believes that at least 14 journalists have been murdered by Isis in Mosul since it took control there last June. Known victims this year include the photographer Adnan Abdul Razzaq, the newspaper editor Thaer al-Ali, and television producer Feras Yasin.

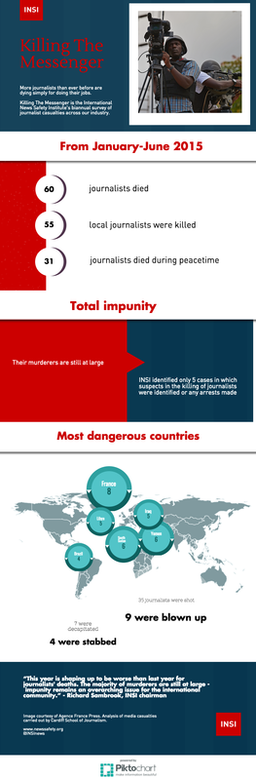

Our newspapers and broadcasters cannot, of course, be expected to record every journalistic death, so it comes as a shock even to those of us within the industry when the figures are collated, as they have been by the International News Safety Institute in conjunction with the Cardiff School of Journalism. INSI's twice-yearly survey Killing the Messenger has just been released, and very sobering it is, too. It reports that 60 journalists and support workers were killed in the first six months of this year.

Some of these deaths received huge attention - the Charlie Hebdo massacre that resulted in France becoming statistically the most dangerous environment for journalists - and the Isis murder of the Japanese freelance Kenji Goto. But when you look at the INSI website - and, indeed, that of the Committee to Protect Journalists - it is doubly shocking to note how little is known about so many of the non-Western victims and how little is done to chase down their killers.

Richard Sambrook, professor of journalism at Cardiff and chairman of INSI, said: “So far this year seven journalists have been decapitated by jihadist groups - a figure unthinkable a few years ago. The consequence of all this is that the public know less about the world than they should, and the killing of journalists is increasingly seen as a political act or means of censorship.”

Sambrook also noted that almost all of those killed had been working locally, and many had been trying to expose crime and corruption.

Across three continents, the modus operandi is remarkably similar: one or two men on a motorbike zoom in and fire a few shots as their target is leaving home, arriving at the office or just waiting at a bus stop. This is international summary "justice" for challenging a politician or crossing a criminal, proof that journalists are not endangered only when working in warzones.

The very high percentage (90%) of deaths in supposedly peaceful areas is - as with the suggestion that France is a riskier environment than Yemen - a slightly skewed statistic. For it is in part a reflection of the fact that many mainstream organisations have pulled out of Syria and Libya because the risk to their staffs has become unacceptable

With the rise of Isis, the West contemplating (and, indeed, taking) military action in the area, and concerns about the masses of people trying to escape from the region to Europe, this is a real problem. We need a much clearer picture from trusted correspondents to inform public opinion about the wisdom or otherwise of decisions being taken in Westminster, Washington and Brussels.

Greste had been in custody for 400 days, most of them before his conviction last summer for helping a terrorist organisation - as the Muslim Brotherhood has now been branded.

His arrest, along with his Al Jazeera English bureau chief Mohammed Fahmy and colleague Baher Mohamed, led to an international campaign under the hashtag "Journalism is not a crime", which saw journalists and media presenters all over the world posing with their mouths taped shut. The focus was on the "AJ three", but other colleagues and students were also in prison. One, in jail without charge, was eventually released after a prolonged hunger strike.

Hopes for justice were not high, especially with judges dispensing death sentences to hundreds of people at a time after ten-minute mass trials. Greste, Fahmy and Mohamed were each jailed for seven years, and Mohamed was given a further three for possessing a bullet. The convictions were quashed in January, Greste was deported and the other two have spent the past two months being retried, with the verdict due on July 30.

In all this, SubScribe is probably telling you what you already know. What you may not know, however, is how many other journalists have been imprisoned in Egypt since the overthrow of President Morsi and the outlawing of the Muslim Brotherhood.

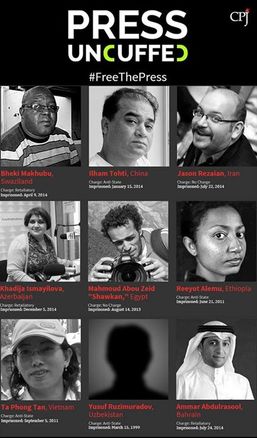

The incoming President al-Sisi promised greater Press freedom, but a survey by the Committee to Protect Journalists last month found that 18 journalists were in jail in Egypt for allegedly "anti-state" activities. Mahmoud Abou Zeid, whom I mentioned at the start of this post, has been in prison without charge for two years.

The CPJ has protested to Egypt about the situation and is also spearheading a campaign called Press Uncuffed to try to secure the release of eight other journalists imprisoned around the world.

Then there are the journalists being held hostage - no one knows exactly how many, but they certainly number in dozens. Among them is Britain's John Cantlie, still in the clutches of Isis and being used as a propaganda pawn, who has told his family to forget him and move on. The whereabouts of the American Austin Tice are still unknown. it's all pretty grim.

Most of us don't face these sorts of dangers doing our jobs, and public sympathy for all journalists has been in short supply since the hacking scandal. Few tears have been shed beyond Fleet Street for those News UK journalists who spent years in limbo in our justice system before being cleared of criminally paying for stories.

It's perhaps wise, therefore, to avoid over-empathising for fear that that could amount to self-aggrandisement. But ours is an honourable and important trade and we should be proud to stand up for it

The Maryland students have also produced bracelets to support the imprisoned journalists, which you can buy here. And the family of Austin Tice has a campaign page that you can support here.

You see, we're not all bad.

Peter Greste background

Abdullah Elshamy released

Commentary: Why we should care about jailed journalists

RSS Feed

RSS Feed