Local newspapers matter

Young reporters need to learn their craft by living and working within the communities they serve

April 12, 2012

When was the last time you - or anyone you know - stood at the gates of a cemetery collecting names of mourners as they left a funeral?

When did you last attend a parish council meeting or magistrates' court? Or call into a local police station for a chat (rather than to hand in your drivers' documents) or check the upcoming weddings at the register office?

Do you still look at the postcards in newsagents' windows and check the village notice board?

Indeed, have you the faintest idea of what I'm on about?

For generations of journalists, being soaked through or bored throughout were the price to be paid to learn their craft. The lessons were given not by university lecturers, but by wiser older hands (sometimes as old as 23) who knew all about the fetes worse than death, that brides were more likely to carry a bouquet of freesias than fuchsias, that rain never dampened the enthusiasm for anything and that the lady mayoress was frequently to be seen sharing a joke. The biggest lesson of all was that faces and names sold papers - and that those names must always be spelt correctly.

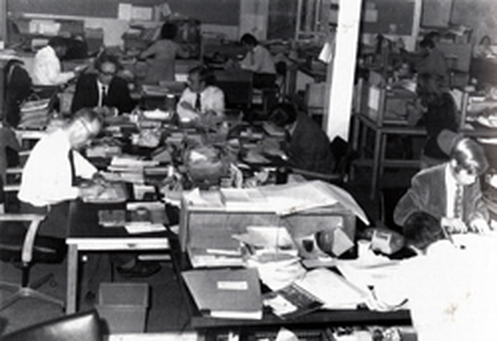

Forty years ago a weekly newspaper serving a medium-sized market town could expect to have a circulation of between ten and fifteen thousand. It would be staffed by an editor, a news editor, a chief reporter, half a dozen reporters, a sports editor, a couple of photographers and three or four subs. There might also be a feature writer, often an older woman working part-time.

Nearly all of the reporters would likely be juniors - indentured trainees who would serve three years before taking their proficiency test. Some would stick to news reporting, others would find a niche in sport or features or even subbing. Some in bigger newspaper groups would move around during their indenture period so that they would taste life on a daily early in their training.

Most would seek to move on once they had that proficiency certificate in their hands. The fundamental skills they had learnt would be expected everywhere; all the ads used the same phraseology: reporters had to have a talent for finding off-diary stories; subs must always be fast and accurate.

The young journalists would move from weeklies to evenings to bigger evenings. Some would choose the executive route and find their place in the community as the editor of the local paper; for others Fleet Street was the dream. The ambitions were equally honourable - if not equally remunerated - and the result was that Britain had a thriving newspaper industry populated by well-trained journalists. (I am talking here about journalism, not about printers, electricians etc and the Mickey Mouse nonsense of the era.)

For those happy to stay in what were then known as the provinces, there were plenty of jobs and opportunities.

You may like to sit down before you read the next par.

In 1970, the Birmingham Evening Mail had a circulation of 400,000 and employed 113 journalists: 30 newsdesk and reporters, 25 district reporters, 23 news subs, 15 features staff, 20 sports staff and 9 photographers.

There are national newspapers today that struggle to match that level of staffing.

Then came the freesheets and the landscape changed.

People are fickle: readers cancelled their orders for the paid-for weeklies and the freebies flourished. Village stringers were as happy to send their snippets to the newcomers as to the old rags - and sometimes preferred to, since the freesheets' smaller staffs (often ad reps doubling up to perform editorial tasks) wouldn't have the time or inclination to rewrite them. As time went by, readers became convinced they were getting something almost as good as they'd always had - and for nothing.

The local press struggled; advertising ratios grew, so that the papers became almost as ugly as the upstart rivals; costs had to be cut. Newspapers which had been run by local businessmen for reasons of altruism or influence were sold into groups that got bigger and bigger. Some paid-fors took the 'if you can't beat them' approach and went free.

The freesheet didn't kill the local rag. It survived to fight another day. But only just. The decline has been relentless, but the smallest thing can still shock. This morning it was not so much the Johnston Press horror, but the announcement of the shortlist for this year's regional press awards that made me sit upright.

There among the nominees is The Birmingham Post, once one of the country's most respected morning papers. And the category? Best weekly newspaper with a circulation of less than 20,000. (Its sister, the Mail with the monster staff and a circulation to match, now sells a tenth of the copies it did four decades ago - and 'sells' is a generous term, since many are given away.)

When was the last time you - or anyone you know - stood at the gates of a cemetery collecting names of mourners as they left a funeral?

When did you last attend a parish council meeting or magistrates' court? Or call into a local police station for a chat (rather than to hand in your drivers' documents) or check the upcoming weddings at the register office?

Do you still look at the postcards in newsagents' windows and check the village notice board?

Indeed, have you the faintest idea of what I'm on about?

For generations of journalists, being soaked through or bored throughout were the price to be paid to learn their craft. The lessons were given not by university lecturers, but by wiser older hands (sometimes as old as 23) who knew all about the fetes worse than death, that brides were more likely to carry a bouquet of freesias than fuchsias, that rain never dampened the enthusiasm for anything and that the lady mayoress was frequently to be seen sharing a joke. The biggest lesson of all was that faces and names sold papers - and that those names must always be spelt correctly.

Forty years ago a weekly newspaper serving a medium-sized market town could expect to have a circulation of between ten and fifteen thousand. It would be staffed by an editor, a news editor, a chief reporter, half a dozen reporters, a sports editor, a couple of photographers and three or four subs. There might also be a feature writer, often an older woman working part-time.

Nearly all of the reporters would likely be juniors - indentured trainees who would serve three years before taking their proficiency test. Some would stick to news reporting, others would find a niche in sport or features or even subbing. Some in bigger newspaper groups would move around during their indenture period so that they would taste life on a daily early in their training.

Most would seek to move on once they had that proficiency certificate in their hands. The fundamental skills they had learnt would be expected everywhere; all the ads used the same phraseology: reporters had to have a talent for finding off-diary stories; subs must always be fast and accurate.

The young journalists would move from weeklies to evenings to bigger evenings. Some would choose the executive route and find their place in the community as the editor of the local paper; for others Fleet Street was the dream. The ambitions were equally honourable - if not equally remunerated - and the result was that Britain had a thriving newspaper industry populated by well-trained journalists. (I am talking here about journalism, not about printers, electricians etc and the Mickey Mouse nonsense of the era.)

For those happy to stay in what were then known as the provinces, there were plenty of jobs and opportunities.

You may like to sit down before you read the next par.

In 1970, the Birmingham Evening Mail had a circulation of 400,000 and employed 113 journalists: 30 newsdesk and reporters, 25 district reporters, 23 news subs, 15 features staff, 20 sports staff and 9 photographers.

There are national newspapers today that struggle to match that level of staffing.

Then came the freesheets and the landscape changed.

People are fickle: readers cancelled their orders for the paid-for weeklies and the freebies flourished. Village stringers were as happy to send their snippets to the newcomers as to the old rags - and sometimes preferred to, since the freesheets' smaller staffs (often ad reps doubling up to perform editorial tasks) wouldn't have the time or inclination to rewrite them. As time went by, readers became convinced they were getting something almost as good as they'd always had - and for nothing.

The local press struggled; advertising ratios grew, so that the papers became almost as ugly as the upstart rivals; costs had to be cut. Newspapers which had been run by local businessmen for reasons of altruism or influence were sold into groups that got bigger and bigger. Some paid-fors took the 'if you can't beat them' approach and went free.

The freesheet didn't kill the local rag. It survived to fight another day. But only just. The decline has been relentless, but the smallest thing can still shock. This morning it was not so much the Johnston Press horror, but the announcement of the shortlist for this year's regional press awards that made me sit upright.

There among the nominees is The Birmingham Post, once one of the country's most respected morning papers. And the category? Best weekly newspaper with a circulation of less than 20,000. (Its sister, the Mail with the monster staff and a circulation to match, now sells a tenth of the copies it did four decades ago - and 'sells' is a generous term, since many are given away.)

Today the local press is facing its greatest fight - but with a much depleted army - and this time everyone is adopting the 'if you can't beat them' line. The combination of a series of recessions and the rise of the internet is a formidable enemy for the local press to confront and few would bet on it emerging triumphant.

The consolidation of small newspaper operations into bigger businesses with shareholders to answer to has removed all romance and sentimentality.The clank of the linotype, the smell of the ink, the thunder of the presses have long since been removed from most offices as pages are sent electronically to printing contractors hundreds of miles away. With profits and circulations falling and debts rising, journalists are under ever greater pressure to work harder and longer. Jobs are being combined (for heaven's sake, even editors are being done away with) and editions cut.

The consolidation of small newspaper operations into bigger businesses with shareholders to answer to has removed all romance and sentimentality.The clank of the linotype, the smell of the ink, the thunder of the presses have long since been removed from most offices as pages are sent electronically to printing contractors hundreds of miles away. With profits and circulations falling and debts rising, journalists are under ever greater pressure to work harder and longer. Jobs are being combined (for heaven's sake, even editors are being done away with) and editions cut.

The Bristol Evening Post is abandoning its Saturday paper. Johnston Press is turning dailies into weeklies and has sent the Editor in Chief of the Scotsman on enforced leave while it decides what to do about him, having abolished his job.

And all the time we are being offered assurances that readers will get the same local coverage across a range of platforms or formats or whichever digital buzzword is in vogue today.

Well, you have to admit that Johnstons have to do something. The Doncaster Star is an evening paper that sells 2,500 copies a night. Yes, 2,500. How can you run an evening paper with such a circulation?

There are big names in the Johnston stable, but all are scoring at a fraction of the rate they enjoyed in their prime. The Sheffield Star sold more than 200,000 in 1970, today its circulation is around 37,000; the Yorkshire Evening Post sold 250,000, today that is down to 35,000. The Halifax Courier, which has been told it is turning into a weekly, is down from 43,000 to barely 15,000.

And all the time we are being offered assurances that readers will get the same local coverage across a range of platforms or formats or whichever digital buzzword is in vogue today.

Well, you have to admit that Johnstons have to do something. The Doncaster Star is an evening paper that sells 2,500 copies a night. Yes, 2,500. How can you run an evening paper with such a circulation?

There are big names in the Johnston stable, but all are scoring at a fraction of the rate they enjoyed in their prime. The Sheffield Star sold more than 200,000 in 1970, today its circulation is around 37,000; the Yorkshire Evening Post sold 250,000, today that is down to 35,000. The Halifax Courier, which has been told it is turning into a weekly, is down from 43,000 to barely 15,000.

Ashley Highfield, right, Johnston's newish chief executive, today spelt out his vision for his local newspaper stable. And what is it? To emulate mumsnet.

Or as he put it, to create "themed digital destinations". Material on similar topics - gardening, football, events, small business news - will be "aggregated and enhanced with social media to create a compelling destination for people interested in that particular niche...websites like mumsnet have exploited this brilliantly and we can too. So our plan is to create several of these new businesses and then promote them on a national basis".

Excuse me? This is the future of your local newspapers? To turn them into online versions of Gardening Weekly or Football World? On a national basis?

Have you not noticed that there are quite a lot of specialist publications and websites out there? With experts writing them rather than shoestring staffs. Why should anyone turn to the Halifax Courier online edition for gardening tips?

Or as he put it, to create "themed digital destinations". Material on similar topics - gardening, football, events, small business news - will be "aggregated and enhanced with social media to create a compelling destination for people interested in that particular niche...websites like mumsnet have exploited this brilliantly and we can too. So our plan is to create several of these new businesses and then promote them on a national basis".

Excuse me? This is the future of your local newspapers? To turn them into online versions of Gardening Weekly or Football World? On a national basis?

Have you not noticed that there are quite a lot of specialist publications and websites out there? With experts writing them rather than shoestring staffs. Why should anyone turn to the Halifax Courier online edition for gardening tips?

Another part of the strategy is to raise the price of the print editions. "Have you ever wondered why," Mr Highfield asks, "we charge 65p for a paper in one part of the country and £1 for a similar product elsewhere. There are many cases where we simply undercharge. Our experience is that price increases do not have an adverse impact on circulation. Consumers will pay up to 95p for a well-produced weekly product."

Right, so when Rupert Murdoch started his price wars, he got it all wrong did he? He could have raised the price and seen circulations remain the same?

Or if Mr Murdoch's experience doesn't convince him, Mr Highfield might care to look at his own group. A while back, the Yorkshire Post raised its price from £1 to £1.10, scrapped district editions and cut the newsagents' margins. The circulation fell. A survey of 1,400 people for the National Federation of Retail Newsagents said that 59 per cent of respondents were put off by price rises and 60 per cent said they were buying fewer paid-for papers than they were last year because of the cost.

And then there is that caveat in Mr Highfield's remarks: people are willing to pay "for a well-produced weekly product". If local offices are being closed (Todmorden, Hebden Bridge and Bridgnorth are all for the chop) and staff being cut, how well-produced will these papers be?

In his 1971 book Provincial Press and the Community, Ian Jackson of Salford University noted that the Cambridge Evening News left routine local news to its weekly sister and found that it assisted sales. "In towns where the weekly is largely a reworking of the previous week's local news as reported in the evening press, sales are often unimpressive," he wrote. The same must surely apply to regurgitating web content once a week.

Right, so when Rupert Murdoch started his price wars, he got it all wrong did he? He could have raised the price and seen circulations remain the same?

Or if Mr Murdoch's experience doesn't convince him, Mr Highfield might care to look at his own group. A while back, the Yorkshire Post raised its price from £1 to £1.10, scrapped district editions and cut the newsagents' margins. The circulation fell. A survey of 1,400 people for the National Federation of Retail Newsagents said that 59 per cent of respondents were put off by price rises and 60 per cent said they were buying fewer paid-for papers than they were last year because of the cost.

And then there is that caveat in Mr Highfield's remarks: people are willing to pay "for a well-produced weekly product". If local offices are being closed (Todmorden, Hebden Bridge and Bridgnorth are all for the chop) and staff being cut, how well-produced will these papers be?

In his 1971 book Provincial Press and the Community, Ian Jackson of Salford University noted that the Cambridge Evening News left routine local news to its weekly sister and found that it assisted sales. "In towns where the weekly is largely a reworking of the previous week's local news as reported in the evening press, sales are often unimpressive," he wrote. The same must surely apply to regurgitating web content once a week.

The whole industry is being squeezed; morale is low across the board. But there are still organisations that want to produce truly local papers for their communities - and even in these tough times, some are seeing benefits that buck the trend.

***Last autumn only three regional newspapers saw their circulations increase and two of them were sisters: Norwich's Eastern Daily Press and Evening News.

In an interview with UK Press Gazette, Don Williamson, the papers' circulation chief, talked about home distribution and other matters that you would expect to concern a man in his position, but he also showed understanding of the editorial ethos. "We want to establish a bigger network of local correspondents and get readers and newsagents to have an affinity and love for the paper and a sense of ownership of everything we do."

Apart from the staff at the Norwich headquarters, including specialists in local government, health, education and crime, the papers maintain eight district offices and a London-based political editor. The editor EDP Peter Waters told Press Gazette that he made it a principle to avoid shock-horror journalism.

"We are still very conscious of providing a comprehensive local news package as well as national and international news, sport and business, We should do everything a national can do, with local news as our USP. We want people to feel upbeat about where they live and they made the right decision to live in Norfolk. We are militantly pro-Norfolk. We run campaigns for people to shop here and holiday here. The papers belong to Norfolk.”

***Last autumn only three regional newspapers saw their circulations increase and two of them were sisters: Norwich's Eastern Daily Press and Evening News.

In an interview with UK Press Gazette, Don Williamson, the papers' circulation chief, talked about home distribution and other matters that you would expect to concern a man in his position, but he also showed understanding of the editorial ethos. "We want to establish a bigger network of local correspondents and get readers and newsagents to have an affinity and love for the paper and a sense of ownership of everything we do."

Apart from the staff at the Norwich headquarters, including specialists in local government, health, education and crime, the papers maintain eight district offices and a London-based political editor. The editor EDP Peter Waters told Press Gazette that he made it a principle to avoid shock-horror journalism.

"We are still very conscious of providing a comprehensive local news package as well as national and international news, sport and business, We should do everything a national can do, with local news as our USP. We want people to feel upbeat about where they live and they made the right decision to live in Norfolk. We are militantly pro-Norfolk. We run campaigns for people to shop here and holiday here. The papers belong to Norfolk.”

***Important update: Don Williamson was sacked a week before he was due to retire in August 2012. He admitted falsifying the circulation figures for the Evening News and Eastern Daily Press. The figures were reaudited in October and showed that News sales had fallen by 6.2% and the EDP's by 6.5%.

Tindle Newspapers are beating the same drum. The company founded and still run by Sir Ray Tindle at 82 operates under the motto "local papers at the heart of the community". The group has more than 200 titles and managing director Brian Doel says: "I am sure we could have saved money across the group, but we've kept each title very local with local editions and subs and reporters as much as possible. they know most about the community they serve."

Now Sir Ray is no latter day saint and people who work for the EDP or the Tindle papers may not feel life is quite as wonderful as their bosses paint; both groups have made cuts and consolidations. But the core function - to produce local papers - remains intact. The shot of the Tindle papers above show how each has retained its identity; they certainly can't be accused of homogeneity.

Some are paid-for, some are freesheets. If you look at an edition online you turn the pages, just like a normal paper. For some you are asked to pay 35p or 40p, others are free.

Now Sir Ray is no latter day saint and people who work for the EDP or the Tindle papers may not feel life is quite as wonderful as their bosses paint; both groups have made cuts and consolidations. But the core function - to produce local papers - remains intact. The shot of the Tindle papers above show how each has retained its identity; they certainly can't be accused of homogeneity.

Some are paid-for, some are freesheets. If you look at an edition online you turn the pages, just like a normal paper. For some you are asked to pay 35p or 40p, others are free.

Compare this with Newsquest, whose huge group includes the clutch of papers that used to be Essex County Newspapers plus the Basildon and Southend-based stable that was once part of Westminster Press.

The ECN group had its headquarters in Colchester, above, where the Evening Gazette and weekly Essex County Standard were based. There were also district editorial offices for weekly papers in Harwich, Clacton, Maldon, Chelmsford and Halstead. All were printed in Colchester. Today the weekly operations have been merged, the Gazette is still produced - but without an editor on site - and, to be fair, it has done well to hang on to a circulation around half the 30,000 it managed at its peak.

Martin McNeill, who trained with the group in the 70s, is now the editorial director, overseeing the production of the Gazette and the Southend Evening Echo from the group's offices in Basildon.

Let's just run through that again: a local daily newspaper being run by an editor working from an office more than 50 miles away from his audience.

The ECN group had its headquarters in Colchester, above, where the Evening Gazette and weekly Essex County Standard were based. There were also district editorial offices for weekly papers in Harwich, Clacton, Maldon, Chelmsford and Halstead. All were printed in Colchester. Today the weekly operations have been merged, the Gazette is still produced - but without an editor on site - and, to be fair, it has done well to hang on to a circulation around half the 30,000 it managed at its peak.

Martin McNeill, who trained with the group in the 70s, is now the editorial director, overseeing the production of the Gazette and the Southend Evening Echo from the group's offices in Basildon.

Let's just run through that again: a local daily newspaper being run by an editor working from an office more than 50 miles away from his audience.

Like everyone else, Newsquest is hoping to capture new readers through its digital output. The lead story on the Gazette's website at lunchtime today was

Mum's heart stops four times and she suffers stroke having twins

There was a photograph of the woman concerned with two children aged, at a guess, between nine and twelve months old. So this is hardly new news. The picture came with three pars of copy telling us about the heart stopping and the hospital's two-hour battle to save her life. The site then guides us to "Special report in today's Gazette". So that's it, that's all you'll learn unless you buy the paper.

Well, it's a strategy of sorts.

Clicking on the 'most read' list at the side, I bring up a story called

Slimmers urged to use new programme

It tells us that the Anglian Community Enterprise is setting up one-to-one classes to advise people on a weight loss programme that has helped 600 people to lose 200 stone over the past year. (That, as a reader points out, is an average of four and a half pounds each). It doesn't tell us what Anglian Community Enterprise is (it's part of the NHS) or that the sessions are free - as are two other programmes that aren't mentioned in the story, which has no byline.

There is a Tesco ad embedded in the the copy; in the centre of the page there is a glittering mirrorball with roller skaters passing by; at the side there are six ads between the various links to other stories, and there are a further four on top of the Gazette masthead. Every one of the ads is moving. It is almost impossible to read anything without being distracted by a flashing word or image. There are only four local stories on the page, but there are links to national news and features.

The Yorkshire Press, which sold 60,000 a night even with the mighty Evening Post as a rival in the Seventies, is also now owned by Newsquest. Its website looks exactly the same with similar national links, although obviously with different local stories. Is this the way we want our local news? Will these templated websites with their dancing ads attract or deter readers?

Mum's heart stops four times and she suffers stroke having twins

There was a photograph of the woman concerned with two children aged, at a guess, between nine and twelve months old. So this is hardly new news. The picture came with three pars of copy telling us about the heart stopping and the hospital's two-hour battle to save her life. The site then guides us to "Special report in today's Gazette". So that's it, that's all you'll learn unless you buy the paper.

Well, it's a strategy of sorts.

Clicking on the 'most read' list at the side, I bring up a story called

Slimmers urged to use new programme

It tells us that the Anglian Community Enterprise is setting up one-to-one classes to advise people on a weight loss programme that has helped 600 people to lose 200 stone over the past year. (That, as a reader points out, is an average of four and a half pounds each). It doesn't tell us what Anglian Community Enterprise is (it's part of the NHS) or that the sessions are free - as are two other programmes that aren't mentioned in the story, which has no byline.

There is a Tesco ad embedded in the the copy; in the centre of the page there is a glittering mirrorball with roller skaters passing by; at the side there are six ads between the various links to other stories, and there are a further four on top of the Gazette masthead. Every one of the ads is moving. It is almost impossible to read anything without being distracted by a flashing word or image. There are only four local stories on the page, but there are links to national news and features.

The Yorkshire Press, which sold 60,000 a night even with the mighty Evening Post as a rival in the Seventies, is also now owned by Newsquest. Its website looks exactly the same with similar national links, although obviously with different local stories. Is this the way we want our local news? Will these templated websites with their dancing ads attract or deter readers?

Local newspapers matter. Royal Mail is not allowed to give up deliveries to homes just because they are difficult to reach; bus companies are not allowed to abandon rural services and cream off the lucrative urban routes; broadcasters are required to maintain levels of local coverage in return for their licences.

I'm not suggesting that newspaper businesses should be regulated in the same way - you cannot force a private enterprise to provide a potentially loss-making service - but I am saying that those rules for the mail, the buses and the TV stations are there because local communities matter. It is important that people are able to keep in touch and feel part of the area where they live, to be able to reach friends and neighbours in person or through letters, papers, phone calls and, yes, online social networks.

To produce a decent local newspaper, the reporters need to have proper contact with their readers and the community leaders. They need to go to those boring council meetings, not just to take notes, but to chat to people afterwards, to get the stories behind the stories. They need to maintain contact with the local police, the village shopkeeper. They need to be in court for all cases, not simply when they've been tipped off that there's an important or juicy one coming up. And if they don't build their contacts they won't even get the tips for those.

We had to fight in the 1970s for the right to remain in council chambers to hear all the discussions. Councils used to be allowed to vote to go into camera and exclude the press without explanation. As a young reporter I had to stand and challenge such a vote when the law changed, to seek an explanation for why what they were about to discuss was not fit for public consumption. The new rules were effective; government became more open.

And now we can't even be bothered to turn up. Or rather we can't afford the time to turn up. If you've got to write up the Basildon charity fun run, the A12 car crash, the Maldon regatta and the Colchester factory strike, you've barely got time to ring the Stebbing parish clerk about last night's meeting, let alone consider attending in person.

So more and more stories are covered on the phone - but the contacts who tell us what happened are the people with the vested interest in seeing the story slanted in a particular way. Justice and democracy at their basic levels are not seen in action.

Local newspapers have always been produced largely by youngsters with aspirations. Those village calls have always been a chore, the staid writing style constraining. But this is about providing a service, about learning to deal with people, about being grounded and disciplined. If local papers become digital wannabe redtops with slang headings and endless celebs, there will be no use for them. And that matters.

It matters because millions of people will be denied basic information about their communities. And it matters because this slapdash approach will drag down the national press. If local papers do not produce decent ethical journalists with basic skills, who will? National papers have set up their own graduate training schemes, but these are open to only a relative handful of the smartest young men and women.

There are 50 applicants for every graduate post - and the universities are turning out far more media graduates than there are journalists employed across the entire industry. That means there's an army of young people with certificates saying they know what they're doing. But how can they find out for real? Everyone can learn a certain amount from the classroom, but there is still no substitute for what used to be called on-the-job training and where are these youngsters going to get that?

How will they learn how to interview a woman whose five-year-old son has just drowned in the village pond? Will they understand the importance of shining a light on what's going on in the Mayor's Parlour?

They need to know.

One day they may be interviewing the woman whose son has just been killed in a terrorist bombing in a shopping centre. Or looking into shady dealings in Downing Street that could bring down a Government.

I'm not suggesting that newspaper businesses should be regulated in the same way - you cannot force a private enterprise to provide a potentially loss-making service - but I am saying that those rules for the mail, the buses and the TV stations are there because local communities matter. It is important that people are able to keep in touch and feel part of the area where they live, to be able to reach friends and neighbours in person or through letters, papers, phone calls and, yes, online social networks.

To produce a decent local newspaper, the reporters need to have proper contact with their readers and the community leaders. They need to go to those boring council meetings, not just to take notes, but to chat to people afterwards, to get the stories behind the stories. They need to maintain contact with the local police, the village shopkeeper. They need to be in court for all cases, not simply when they've been tipped off that there's an important or juicy one coming up. And if they don't build their contacts they won't even get the tips for those.

We had to fight in the 1970s for the right to remain in council chambers to hear all the discussions. Councils used to be allowed to vote to go into camera and exclude the press without explanation. As a young reporter I had to stand and challenge such a vote when the law changed, to seek an explanation for why what they were about to discuss was not fit for public consumption. The new rules were effective; government became more open.

And now we can't even be bothered to turn up. Or rather we can't afford the time to turn up. If you've got to write up the Basildon charity fun run, the A12 car crash, the Maldon regatta and the Colchester factory strike, you've barely got time to ring the Stebbing parish clerk about last night's meeting, let alone consider attending in person.

So more and more stories are covered on the phone - but the contacts who tell us what happened are the people with the vested interest in seeing the story slanted in a particular way. Justice and democracy at their basic levels are not seen in action.

Local newspapers have always been produced largely by youngsters with aspirations. Those village calls have always been a chore, the staid writing style constraining. But this is about providing a service, about learning to deal with people, about being grounded and disciplined. If local papers become digital wannabe redtops with slang headings and endless celebs, there will be no use for them. And that matters.

It matters because millions of people will be denied basic information about their communities. And it matters because this slapdash approach will drag down the national press. If local papers do not produce decent ethical journalists with basic skills, who will? National papers have set up their own graduate training schemes, but these are open to only a relative handful of the smartest young men and women.

There are 50 applicants for every graduate post - and the universities are turning out far more media graduates than there are journalists employed across the entire industry. That means there's an army of young people with certificates saying they know what they're doing. But how can they find out for real? Everyone can learn a certain amount from the classroom, but there is still no substitute for what used to be called on-the-job training and where are these youngsters going to get that?

How will they learn how to interview a woman whose five-year-old son has just drowned in the village pond? Will they understand the importance of shining a light on what's going on in the Mayor's Parlour?

They need to know.

One day they may be interviewing the woman whose son has just been killed in a terrorist bombing in a shopping centre. Or looking into shady dealings in Downing Street that could bring down a Government.