The Press under siege: how the police, politicians, pressure groups and even publishers are attacking British journalism

We are unlikely to be kidnapped and murdered on the school run or imprisoned for writing stories that displease the Government, but journalists in Britain have plenty to be worried about. The following article is an updated (and Anglicised) version of a portrait of the situation in the UK written for the New York-based Committee to Protect Journalists' annual "Attacks on the Press" book.

Friday 1 May, 2015 Andrew Norfolk was driving to an appointment five years ago when he heard a radio news report that a gang of men had been convicted of the systematic sexual abuse of a teenager. In the split second before the men were named, Norfolk thought “They will be Asians.”

He was right. And he was troubled by his instinctive response. Norfolk is The Times’s correspondent in the North of England, where there had been of a handful of court cases involving gangs preying on young girls. Now he detected a pattern: the gangs were Asian, their victims white. This was not going to be an easy story to tell. The Times editor James Harding – now head of news at the BBC – told Norfolk to focus exclusively on the story for as long as it took to get justice for the children. What he discovered worried him as much, if not more than, the gangs’ crimes. After detailing the plight of a 12-year-old girl from Rotherham, Norfolk received a bundle of confidential police and social services files showing that they had known for more than a decade what was going on. “They knew the names of the men, the girls, and the places they were taken. They had effectively sat back and done almost nothing to stop it,” Norfolk told the British Journalism Awards (BJA) ceremony last December, when he was named journalist of the year. “We published the story...I thought those at the top of each organization would be so horrified that they would immediately seek to establish what could have gone so terribly wrong. “Instead they seemed interested only in discovering how we got hold of the documents. The council had already threatened High Court action to block an earlier story. Now it demanded a criminal inquiry into the leak. It also hired a firm of solicitors to expose the ‘security breach’. “ Norfolk carried on digging and Rotherham was eventually shamed into commissioning a public inquiry, which published its report last August. It found that at least 1,400 children had been abused over a 12-year period and that official failings had been “blatant”. Another perspective

The night after Norfolk was presented with the BJA award - to go alongside the Orwell Prize and Paul Foot award he had already won for his work in Rotherham - another group gathered to consider the state of British journalism. Here, an audience listened to a Labour MP accuse owners and editors of “the big papers“ of propagating the myth that their journalism held the powerful to account.

“They have operated like a Mafia, intimidating here, bribing there, terminating careers and rewarding their most loyal operatives and toadies,” Tom Watson said. “For years they could fix any legislation that affected them, in a way that no other industry could. But it didn’t stop there. Their influence was so great that for many, it became impossible to know who was really running the country.” Naming the proprietors of The Sun, Times, Daily Mail, Daily Express, Daily Star, Daily Telegraph, Daily Mirror and their Sunday stablemates (omitting only The Guardian, Independent and Financial Times from his attack) and addressing their editors, Watson declared: “Where there is a threat to freedom it comes from you. You have shown again and again that you don’t care about freedom of expression. “You have never told the truth about your wrongdoings and you do all you can to suppress the reporting of them. “You don’t care about the freedom of journalists to report on systematic intrusion into all our lives by the security services...You don’t care about the freedom that ordinary British people should enjoy from cruel treatment by your employees...The only freedom you care about is your own, to do exactly what you like, without consequences. “ Watson was delivering the second Leveson Anniversary lecture, an event organised by Article 19 and the Media Standards Trust to mark the publication of Sir Brian Leveson’s report on his inquiry into the Press, which was established in the wake of the News of the World phone hacking scandal. The audience included members of the Hacked Off group, many of whom had their voicemail intercepted by the News of the World, and which now campaigns for tougher press regulation. Watson, co-author of a book about the hacking saga entitled Dial M for Murdoch. told them that, in his view, a small group of media moguls, executives and senior journalists had become “the power in this country”. Siege mentality

That is not a view that most British journalists recognise. For, as in other countries, UK journalism is a trade under siege. Police, Parliament, pressure groups, public relations people and even publishers are undermining the ability to report.

As Roy Greenslade, a former Daily Mirror editor who is now a lecturer and commentator, told CPJ: “There is a growing feeling that the Press has become too powerful, which is strange because it is actually weaker than it has been at any time in its history.” Since the Guardian’s phone hacking investigation blew up in 2011 (just in time to scupper News Corp’s bid to take over the bit of BSkyB that it didn’t own):

These developments are all directly linked to the hacking scandal, and many have public support, but there have been less overt and possibly more dangerous assaults on the freedom of the Press. Hidden dangers

The two most worrying trends are the use of legislation initially designed to counter terrorism to spy on journalists’ phone and email records – and hence uncover their sources - and the advance of an army of public relations staff who hamper journalists’ efforts to build proper relationships with people in authority.

In a speech to the newsvendors’ charity NewstrAid in October 2014, the Daily Mail editor Paul Dacre also identified threats from Europe “in the grizzly shape of the right to be forgotten” [an EU ruling that has led Google to remove certain details, including criminal convictions, from search results], threats “to the sanctity of our content by the undermining of copyright protection” and threats to the local press “from the taxpayer-funded BBC”. Dacre further predicted a “defamation derby for all those who want to gag or punish the press” as a result of the royal charter. [No regulator has yet emerged to seek recognition under the charter, but if one appears, then any news organisation that declines to accept its authority and inherent arbitration service will put itself at risk of having to pay both parties’ costs in any dispute that goes to court - even if it wins the case. This is a particular concern for local newspapers.] There were wry smiles when a transcript of Dacre’s speech was published, not least because he presides over the UK’s most complained about and most censured news organisation - and the industry regulator's ethics committee. Hacked Off – which he characterised as “a tiny, unrepresentative pressure group run by zealots, priapic so-called celebrities, and small-town academics [who had] united to cast the debate as a biblical fight to the death between good and evil, with the Press cast in the role of the devil” – produced a point-by-point rebuttal. Pushing the self-destruct button

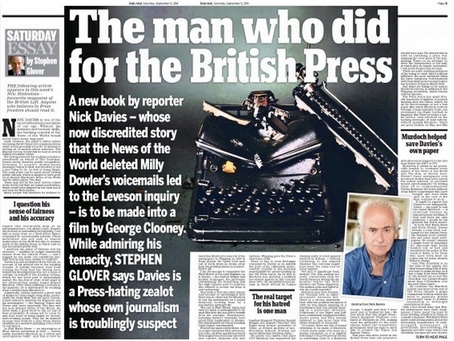

Others noted the Mail’s antipathy to the Guardian: after the phone-hacking trial of Rebekah Brooks and Andy Coulson ended, it published an essay casting the man behind the paper’s investigation as “the man who did for the British Press”, and it has branded Edward Snowden a traitor for his NSA revelations, published in the UK in the Guardian.

Aside from the Mail's dog-eat-dog assaults on the Guardian and the BBC, the British newspaper industry sometimes seems intent on destroying itself with round after round of redundancies coupled with ever-growing workloads that make the practice of journalism increasingly difficult. The Telegraph's editorial strength has been halved over the past nine years. The Express set out last year to get rid of 200 of its 650 journalists - even though the paper and its Star stablemate are profitable and its owners Northern and Shell turned a £5.6m loss into a £37m operating profit last year. There are similar, though less draconian, examples across what used to be known as Fleet Street. In the regions the situation is even grimmer. Few independent local papers survive as most of the country is carved up between Newsquest, Trinity Mirror and Local World, each of which is relentless in its pursuit of savings. Reporters no longer routinely live and work in the communities they serve, but instead operate out of towns miles away. Subs meanwhile work in "hubs" hundreds of miles from the reporters, producing dozens of papers to centrally designed templates. Even editors are being dragged further and further from their readers as they are expected to take responsibility for titles covering anything up to three counties. Barely a day goes by without Hold the Front Page reporting the departure of yet another long-serving editor. This week, for example, Newsquest has announced plans to make 30 journalists, including four editors, redundant. The group's papers include titles set up in the last century - or even the century before that - by families with ink in their bloods. It is now owned by the American group Gannett, whose chief executive Gracia Martore had a pay package worth more than £8m last year, according to Bloomberg. Police v the Press

So much for self-inflicted wounds. When it comes to attacks from outside the industry, the greatest concern for most journalists has been the collapse of trust between the police and the Press, at both local and national level.

As Roy Greenslade says: “We are seeing played out in front of our eyes an amazing war between police and journalists.” He put this down to police embarrassment over a series of blunders, including:

Long gone are the days of the desk sergeant showing his day-book to a reporter who drops by the local police station for a cup of coffee and a chat each morning. Information is now funnelled through PR people, so that building up a rapport with contacts becomes increasingly difficult. This is true in almost every area of public life. The trade magazine Press Gazette reported last year that 1,500 communications staff were employed across 20 central government departments and today it says that police forces spend £36m a year on PR and communications. Parish councillors have been told not to talk to reporters without clearing what they have to say with the council clerk; people serving in the Forces have to report all encounters with journalists, even if they are family or friends in a social setting. Press Gazette editor Dominic Ponsford says: “PRs stopping journalists having healthy relationships with all sorts of people is infantile. We’re in a weird, warped place where police regard an officer speaking to a journalist without permission as a serious crime. But if the police and journalists are at war, it’s a bigger problem for the police than the press because a frosty relationship doesn’t help them to get their information out.” The march of the PRs means that covert contacts and whistleblowers have become even more important to journalists researching public interest stories. That, in turn, makes the protection of those sources ever more vital. The grim RIPA

The Regulation of Investigatory Powers Act was passed in 2000 to combat a perceived terrorism threat. It allowed public bodies to conduct surveillance and access computer and telephone records in the interests of national security or to prevent serious crime.

Before long, however, local councils were spying on families for such trivial reasons as to check that they were putting their dustbins out on the right day. The rules were tightened so that a magistrate had to authorise council use of the powers, but police still needed only to approach a senior officer. Official statistics show that about half a million applications a year are made to access data under the act. And while that may be regarded as a worrying sign of a surveillance society, the headline concern recently has been over the way the act was being used against journalists. Even Hacked Off, which has fought the press over phone hacking, through the Leveson inquiry, and over the establishment of a new regulator, is on the newspapers’ side and joined the call for a change in the law. The police may have been looking only at records of calls made, rather than listening to their content, but George Brock, former head of journalism at City University in London, says that served to underline the importance of metadata. "When Edward Snowden started releasing material showing the scale of NSA and GCHQ surveillance, the line from the authorities was, ‘We’re not reading emails or listening to calls. We’re looking at metadata.’ Well, you can learn a hell of a lot about a person – and their sources – if you know who they’re talking to, when and how often.” Brock is a trustee of the Bureau of Investigative Journalism (BIJ), which submitted a case to the European Court in Strasbourg last August arguing that the use of Ripa to monitor journalists’ phone calls was contrary to Article 10 of the European Convention on Human Rights, which protects freedom of expression. The action coincided with the CPJ’s “right to report” petition urging U.S. President Obama to ban the surveillance of journalists and the hacking of their computers. Plebgate and Chris Huhne

The two most notorious examples of the way RIPA has been used to identify journalistic sources relate to political stories in the Sun and Mail on Sunday.

Tom Newton Dunn, the Sun’s political editor, broke the story that became known as Plebgate, after a senior government minister was accused of swearing at police officers who refused to allow him to ride his bicycle through the main gates at the end of Downing Street rather than use the pedestrian entrance. Andrew Mitchell, above, was eventually forced to resign over the incident and has since lost a libel action against the Sun that is expected to leave him £3m out of pocket. The Metropolitan Police went through Newton Dunn’s phone records to discover who had leaked the story. As a result, three officers were sacked for gross misconduct – even though Crown Prosecution Service decided that they should not be charged because there was a public interest in the events of that night being made known. A fourth officer was jailed for giving a dishonest account of the incident, having lied about having witnessed it. The whistle-blower, who now works as a car salesman, told the Sun that the case had cost him his career and his marriage and had left him £13,000 in debt, but that he had no regrets.“I’d do it again tomorrow,” he said. “I thought the public had a right to know how someone that senior in the Government behaved.” In the case of the Mail on Sunday, Kent police went through phone records of the news desk and a freelance reporter to find out the source of its story about Energy Secretary Chris Huhne having persuaded his wife to take his speeding penalty so that he would not lose his driver’s license. The checks were made and the results passed to prosecution lawyers despite a judge’s ruling that the newspaper’s sources should not be disclosed. The minister, his wife and the source – a judge who was eventually found to have lied to the police - all ended up in jail.

After the Newton Dunn disclosure, the Press Gazette began campaigning for the law to be changed so that a judge had to give permission for RIPA to be used. Ponsford also sent freedom of information requests to every force in the country asking about its use of RIPA. Most refused to say. The Interception of Communications Commissioner issued similar requests with greater success. He reported in February that police had accessed the communications data of 82 journalists over the previous three years on the say-so of senior officers, even though most of their applications did not justify such action. The result was that 68 sources were charged with criminal offences and 15 lost their jobs. Even before the commissioner reported, politicians of all parties had backed Press Gazette’s campaign and the Home Office indicated in October that the code would be changed by Christmas. It announced in December, however, that the only alteration would be the requirement for police to note when checks were made on the phone or email records of journalists, lawyers, doctors, MPs or the clergy. Senior would still be able to approve the check without outside authority. The commissioner recommended, however, that while police were not "randomly trawling" journalists' communications records, a judge should have to approve access to such data where the objective was to uncover a journalist's source. A statutory instrument was passed in March to put that provision into law and new legislation is expected in the next Parliament.

The success of Press Gazette's Save Our Sources campaign was a personal triumph for Ponsford, left, who had wanted a journalist’s relationship with a source to be in a special category regarding confidentiality, so that it was treated the same way as those between solicitor and client or patient and doctor, but the proposed adjustment would not give the records that privilege .

“Journalists having their privacy invaded isn’t the worst horror in the country,” he said. “People have little sympathy with journalists after the News of the World listened to people’s voicemails. But our concern is not for the journalist but for the sources. “If police can look at journalists’ phone records secretly and at will, it puts all sources and whistleblowers at risk. Without those, there can be no investigative journalism, and without investigative journalism, there will be more corruption and wrongdoing in public institutions.” Others are less convinced about making special provisions for journalists, who are, after all, supposed to have the same rights and responsibilities of any citizen. Brock prefers the idea of a better and stronger protection of the public interest: “I’m in favour of legally protecting disclosures which can be judged in the public interest, because laws organised around that principle don’t get into the complication of trying to establish who’s a journalist and who isn’t,” He cited the case of David Miranda, who was detained at Heathrow while carrying Edward Snowden’s NSA material to his journalist partner Glenn Greenwald, and the question of whether he could be regarded as being involved in a journalistic endeavour. Gavin Millar QC the barrister who is leading the BIJ case in Strasbourg, is in favour of a shield law for journalists of the kind seen in some U.S. states. He told a gathering of editors in November, “We need a free-standing law that protects confidential information and confidential sources and that judges and law enforcement agencies cannot by-pass or miss because it is sitting there in front of their faces in black and white." The local newspaper reporter

Millar told the Society of Editors that police had been abusing surveillance powers since 2008, when Sally Murrer of the Milton Keynes Citizen was charged with aiding and abetting misconduct in a public office after police bugged her conversations with a detective sergeant who was a friend and former lover.

The officer was suspected of passing her information and she was accused of paying him for it. The reporter was strip-searched and told she would go to prison. The case was thrown out when it came to court. Papers relating to the authorisation for the bugging did not mention that Murrer was a journalist or that the intention was to identify a source. "This was a startling omission because the right of the journalist to protect the identity of such a source is strongly protected in our law and in European Human rights law,” Millar said. “It can only be overridden if a judge decides that there is an even more important public interest requiring the source to be identified -- and that the evidence being sought cannot be obtained in some other way. Examples of such an overriding public interest might be the need fully to investigate terrorism or serious organised crime." Millar said the case should have caused alarm, yet the situation has got much worse since. He also noted that the charge against Murrer – misconduct in a public office – was a novel one against a journalist. Previous unsuccessful attempts to prosecute journalists in this sort of situation had alleged that the journalist had acted corruptly, as defined by a 1906 statute. Misconduct in a public office was a vague charge based on a very old [13th century] common-law offence without the clear elements of modern statutory criminal legislation, he said. The charge was, however, now being used routinely against journalists suspected of making illegal payments to contacts who work in the public sector. Phone hacking and UK's biggest police operation

The most obvious front in the conflict between journalists and the police has been the clutch of investigations arising from the phone-hacking saga and a series of prosecutions for historic alleged offenses.

In 2006, a News of the World reporter and a private investigator were jailed for hacking into Prince William’s voicemail. The paper’s owners, News International – which also owns the Sun, Times and Sunday Times - insisted that this was a case of one “rogue reporter” and Scotland Yard officers charged with investigating any wider criminality accepted that assurance. The force’s embarrassment over its failure to probe more deeply has been seen as one explanation for the scale of the investigations started after the scandal blew open five years later when Nick Davies of The Guardian reported that the News of the World had intercepted the voicemail of Milly Dowler, above, a schoolgirl who was later found murdered. That disclosure caused mayhem. The police were embarrassed. David Cameron, who had installed the News of the World’s former editor Andy Coulson in 10 Downing Street as his director of communications, was embarrassed. Murdoch was embarrassed. In his panic, the Prime Minister ordered the Leveson inquiry. The Metropolitan Police Commissioner – Britain’s most senior police officer - resigned. Murdoch, who had long wanted to replace the paper with a Sunday edition of The Sun, closed the News of the World. The BSkyB bid was dead in the water and in New York, the stock value of News International’s parent company, News Corp, plummeted. Company lawyers were concerned that the scandal would cross the Atlantic and lead to corporate charges that would threaten the entire business. To appease them, a “management and standards committee” was set up at News International’s Wapping HQ. Millions of documents were offered to the police. As Dominic Ponsford put it, the foot soldiers were thrown to the wolves, while Rebekah Brooks, a former editor of the News of the World and the Sun who had risen to become News International’s chief executive, left with an £11m payoff. Fuelled by the News International dossier, the police operations spawned by the scandal combined to become Britain’s biggest criminal investigation yet. The cost to the taxpayer has been put at more than £40m and even now, three years after the closure of the News of the World, there are still a hundred officers working on the inquiries full time. Sixty-four journalists have been arrested and more than 100 questioned under caution by officers working on operations known as Weeting (phone hacking), Elveden (paying public officials) and Tuleta (computer hacking). In August 2014 Coulson was jailed for 18 months after being found guilty of conspiracy to intercept voicemails. Three senior journalists were given shorter sentences; two others and a private investigator were given suspended sentences. Rebekah Brooks was found not guilty of all charges, as were her husband, secretary, security chief and former managing editor Stuart Kuttner. Paying public officials for tips

Elveden prosecutions have tended to involve the same charge that Sally Murrer faced: aiding and abetting or conspiracy to commit misconduct in a public office. To date, only two journalists have been convicted of this offence and both convictions were overturned on appeal. Thirteen journalists have been cleared and juries were unable to reach a verdict on eight others. The reluctance of juries to convict prompted a wholesale review of Elveden cases and now the prosecutions of all but three journalists have been abandoned. A number of police, prison officers and soldiers have, however, been jailed for accepting money for stories and the cases against other sources are continuing.

While paying for stories is generally regarded as taboo in countries such as the US, there is a long tradition in Britain of rewarding contacts with a drink, tickets to a sporting fixture or hard cash. The Bribery Act of 2010 changed the landscape, but before that few journalists had any idea that it was against the law to pay whistle-blowers for information. Even the journalist’s legal bible, Essential Law for Journalists, did not mention that paying officials for stories was illegal, though it specifically states that witnesses in trials and criminals should not be paid. Trevor Kavanagh, associate editor of the Sun, has been forthright in his condemnation of the police investigations, which he and many others regard as disproportionate. (This is not a view shared by Hacked Off, which takes the position that sections of the press are irresponsible and should be reined in.) “Their alleged crimes amount to writing or paying for stories the authorities wanted kept under wraps,” Kavanagh wrote. “The cost to taxpayers is stupendous…The cost in wrecked private and professional lives is beyond calculation. And for what? The stories were all true. They were stood up. Nobody in the prison service, health service or HM Treasury ever complained to the police or to the newspapers involved. There were no leak inquiries.” Lives in limbo on police bail

Just as the use of RIPA to spy on journalists revealed the extent to which ordinary people are being put under surveillance, so the treatment of the journalists arrested in the post-hacking police operations has exposed how thousands of lives are left in limbo while police and prosecutors decide whether to bring them before the courts.

The News of the World crime reporter Lucy Panton, above, was on maternity leave when her paper was shut down in July 2011. She was arrested the following December over alleged payments to police. She was charged 19 months later and went on trial last year, becoming the first journalist to be convicted on charges relating to misconduct in public office. Her successful appeal this year led to the review of all Elveden cases and she was formally acquitted in April, 40 months after her arrest. This long gestation period – which the police put down to spending cuts and lack of resources - has been common in the cases of journalists accused of hacking or paying officials. Neil Wallis, a former deputy editor of the News of the World who worked as a PR consultant for the Metropolitan Police, was arrested on suspicion of phone hacking in July 2011 – the month the Milly Dowler story broke and the paper was closed. He was on police bail until February 2013, when he was told no action would be taken against him. He was rearrested last year and is now awaiting trial, three and a half years after his initial arrest. Journalists are in a position to attract attention to such cases and argue that “justice delayed is justice denied,” but they are not alone in being trapped in this way. According to the BBC, an estimated 72,000 people are in a similar situation, of whom more than 5,000 have been on police bail for more than six months. Teachers and social workers, for example, are routinely suspended from work for months or years while they wait to learn whether they are to be prosecuted. And in many instances, the cases are quietly dropped without their ever going anywhere near a court. Campaigners from all political parties are now lobbying for a law to restrict to 28 days the time someone can be kept on police bail. A third of the journalists arrested in the Weeting, Elveden and Tuleta operations were cleared after months on police bail. Four from the Mirror group – including two who were serving Sunday newspaper editors - are still in limbo 21 months after their arrests. Local skirmishes

Ripa and the hacking investigations have been the bloodiest battles in the conflict between journalists and police, but there has also been some hand-to-hand fighting.

1: Secret database Half a dozen journalists are taking the Met to court after discovering that its “domestic extremists” database contains more than 2,000 references to journalists, logging their professional activities, their appearance and details including families’ medical histories. The six, five of whom have previously won apologies or compensation from the police for assault or unlawful searches while they were doing their jobs, want the files destroyed. 2: ‘Excess phone data’ The chief executive of News UK (formerly News International) has protested to Vodafone and the police after the discovery that more than 1,750 mobile phone records of journalists, lawyers and secretarial staff had been passed to police in error. The police had sought one reporter’s record as part of an investigation and Vodafone mistakenly sent the entire database, covering just about everyone who had a company phone between 2005 and 2007. The Met transferred the material to CDs, made a spreadsheet and checked on five other journalists before reporting that it had been given “excess data” and surrendering the records - seven months after Vodafone first noticed the error and asked for their return. Ponsford of Press Gazette compares this with the case of Nick Parker, who was convicted last year of handling an MP's stolen mobile phone: “The reporter has a look at the phone, hands it in the next day, doesn’t write a story – and ends up in court.” Speaking at the BJA awards night, Andrew Norfolk mourned the change of environment: “Senior officers you once had a relationship with based on what you thought was mutual trust and respect suddenly too scared to speak to you, or perhaps it’s not that, they’ve just got so much on, the poor dears: planning your arrest, wading through your phone records, I think it’s 1,700 phones from my company alone.” 3: Harassment orders In November 2014, a former UK Independence Party press officer called Jasna Badzak was sent a “cease and desist” notice by the Metropolitan Police alleging that she had harassed another former party worker “by providing information to reporter Glen Owen [of the Mail on Sunday] of a false nature” which had resulted in “victim being subjected to numerous phone calls and e-mails”. Owen had made one phone call and sent three emails to the complainant to check on information given to him by an entirely different source. Earlier in the year, Gareth Davies, a local newspaper reporter, was served with a similar notice by three policemen from the Met who visited the Croydon Advertiser office. It required him to stop “harassing” a conwoman who had complained that he had contacted her by Twitter and email to ask her about allegations made against her. She was subsequently jailed for 30 months for a $360,000 fraud , but the harassment notice was not rescinded. Hunt the whistle-blower

Last December The Sun splashed on a story about a Conservative MP playing Candy Crush on his iPad during a Commons committee meeting discussing pensions. The MP, Nigel Mills, apologised and will face no further action – but the House of Commons ordered an investigation to find out who took the incriminating photograph published on the paper’s front page.

Press Gazette has noted a growing number of internal leak investigations by public authorities and in December it reported that the Metropolitan Police had conducted 300 such inquiries, most of them using RIPA, over the previous five years – not all relating to the disclosure of information to the Press. Five central government departments had held 60 leak investigations over the same period. The government has promised protection for whistle-blowers, but there has been little evidence of that to date. The pledge was made after the daughter of an elderly patient exposed lethal failings at her local hospital in Mid-Staffordshire. Julie Bailey was threatened, abused and eventually had to move house, but her determination led to a public inquiry which found that up to 1,200 patients may have died needlessly because of the poor treatment and neglect at the hospital. Yet stories continue to emerge of whistle-blowers being disciplined, sacked for misconduct or hounded out of their jobs. As the Candy Crush Saga MP and Andrew Norfolk’s experience demonstrate, the default position is often not to address the problem, but to order an investigation into who let the cat out of the bag. The day after its Candy Crush splash, the Sun ran a leader saying: "This is Britain since the Leveson Inquiry, that declaration of war on the press by the elite we are here to hold to account. "Leveson’s biased witch-hunt empowered them to try to stop the press revealing inconvenient truths the public has a right to know. "One MP playing Candy Crush isn’t the biggest scandal ever — and we welcome that Mr Mills had the good grace to own up and swiftly apologise. The authorities’ reaction, though, is of graver significance." Nor are those with something to hide the only ones to indulge in hamfisted censorship. In his acceptance speech at the British Journalism Awards, Andrew Norfolk, above, said that Sir Brian Leveson had invited newspapers to submit their best examples of public interest journalism to his inquiry.

The final report had rightly condemned much that was wrong in the world of newspapers, Norfolk said. But it had also significantly contributed to the entire profession being held in what sometimes feels like lazy, near-universal contempt. The examples of public-interest journalism were “buried in a tiny section of the 2,000-page report labelled good practice – Sir Brian’s fleeting concession to the possibility that not everything we do as journalists is sleazy and wrong”. Norfolk continued: “The judge said that he had omitted one or two because they were not without controversy. “I wish he were here tonight because I would like to have told him ‘You know, Brian, sometimes it’s the uncomfortable truths, those not without controversy, that are the most important for a journalist to tell, even if they cause discomfort to a High Court judge, because they’re so often the stories — like Rotherham — that those in authority least want us to reveal.’ “A free society needs an unshackled press. For years there were people in Rotherham, desperately concerned about what was happening, who tried their best to raise the alarm. Frontline youth workers told their bosses, parents pleaded with police. “Reports were written, seminars held, letters sent to chief constables, MPs and government departments. Nothing happened. Nothing changed. When all else failed, someone very brave decided to put their trust in our derided profession. And finally the truth came out. “As requested, The Times sent five stories to the Leveson inquiry. He accepted four of them. All but one. And, you know, I really am quite proud to be able to stand here this evening and say: ‘guess which one he chose to discard?’” |

|

|

How you can be a SubScriber

|

Sign up for email updates (no spam, about one a month)...

|

|

...make a financial contribution

I'd like to subscribe

There will never be a charge for reading SubScribe,

but if you would like to make a donation to keep it going, you can do so in a variety of ways by pressing this button. Thank you. |