Why local newspapers have to change

Montgomery is right to ditch the traditional model, but crowd-sourcing news may not bring the result he wants

May 22, 2013

Listening to newspaper veterans trying to use digispeak can be as toe-curling as hearing grandad rap with a 15-year-old. The words don't sit easily on their tongues. But listen we must because they are trying to get their heads round the future. And that is bloody hard.

David Montgomery has scared a lot of people with his latest pronouncements about Local World, his stable of more than 100 local papers. Embracing the jargon of the internet age, he has painted a futureworld where editors will be 'directors of content', journalists will be 'harvesters of content' and 'much of the human interface' involved in local news publishing will disappear.

Montgomery has a history of scaring people, having taken a scythe to much of Fleet Street over the years - a consistent cold-blooded cost-cutter, as Roy Greenslade described him. Now he has turned to the regional press, and his evidence to the Commons culture, media and sport committee this week sent many running for cover. The 'middle ages' model of a reporter going out on one story a day and returning to the office to write it up was highly wasteful and unsustainable. Journalists would have to develop new skills and take more responsibility for publishing their work in print and online.

To use such language is bound to be frightening in an era when every news organisation is cutting so hard that papers are produced by one woman and her cat working from the local library. 'What more does he want us to do?' you can hear reporters cry. 'We're already manning reception, taking photographs and sweeping the floor when we should be getting stories.' Meanwhile subs crouch under the table as they are once again identified as an endangered species.

There are economic truths that have to be acknowledged and dealt with. Traditional news operations are struggling and will continue to struggle until they not only up their game, but change it. The first thing they have to learn, God help us, is to communicate - and that means listening as well as talking.

For the past five years, journalists in every kind of newsroom have heard nothing but cuts and job losses, coupled with demands that the survivors work on more and more platforms. The writer has to report, analyse, stand in front of a video camera and then tweet repeatedly. The sub has to prepare the resultant copy for print, web, tablet and mobile (often using four different pieces of software). Everyone feels overworked and under-appreciated. Everyone is fretting that quality is slipping. And the declining circulation figures are there for all to see.

Montgomery's vision for his Local World group may be scary. But at least it's a vision. And at least he is trying to communicate it - the trouble is, he isn't doing that very well. And his hard-man record does him no favours. What he is saying is that local newspapers are important (as SubScribe wrote last year) and that they can become profitable, but that they have to be run in a different way.

Listening to newspaper veterans trying to use digispeak can be as toe-curling as hearing grandad rap with a 15-year-old. The words don't sit easily on their tongues. But listen we must because they are trying to get their heads round the future. And that is bloody hard.

David Montgomery has scared a lot of people with his latest pronouncements about Local World, his stable of more than 100 local papers. Embracing the jargon of the internet age, he has painted a futureworld where editors will be 'directors of content', journalists will be 'harvesters of content' and 'much of the human interface' involved in local news publishing will disappear.

Montgomery has a history of scaring people, having taken a scythe to much of Fleet Street over the years - a consistent cold-blooded cost-cutter, as Roy Greenslade described him. Now he has turned to the regional press, and his evidence to the Commons culture, media and sport committee this week sent many running for cover. The 'middle ages' model of a reporter going out on one story a day and returning to the office to write it up was highly wasteful and unsustainable. Journalists would have to develop new skills and take more responsibility for publishing their work in print and online.

To use such language is bound to be frightening in an era when every news organisation is cutting so hard that papers are produced by one woman and her cat working from the local library. 'What more does he want us to do?' you can hear reporters cry. 'We're already manning reception, taking photographs and sweeping the floor when we should be getting stories.' Meanwhile subs crouch under the table as they are once again identified as an endangered species.

There are economic truths that have to be acknowledged and dealt with. Traditional news operations are struggling and will continue to struggle until they not only up their game, but change it. The first thing they have to learn, God help us, is to communicate - and that means listening as well as talking.

For the past five years, journalists in every kind of newsroom have heard nothing but cuts and job losses, coupled with demands that the survivors work on more and more platforms. The writer has to report, analyse, stand in front of a video camera and then tweet repeatedly. The sub has to prepare the resultant copy for print, web, tablet and mobile (often using four different pieces of software). Everyone feels overworked and under-appreciated. Everyone is fretting that quality is slipping. And the declining circulation figures are there for all to see.

Montgomery's vision for his Local World group may be scary. But at least it's a vision. And at least he is trying to communicate it - the trouble is, he isn't doing that very well. And his hard-man record does him no favours. What he is saying is that local newspapers are important (as SubScribe wrote last year) and that they can become profitable, but that they have to be run in a different way.

If we stop and think about this calmly, it is only common sense. You can't keep piling extra work on a dwindling staff without reorganisation. But it has to be thought-through reorganisation, not simply random mergers of departments, editions, papers as is happening now. Managements at all levels have given the impression that the only tool they are capable of using is the knife, and subs fear that they are next for the chop. It's hardly surprising that you hear old hacks moaning 'They got rid of the typesetters, the printers, the proof readers, now they're going to get rid of us.'

The entire structure and hierarchy has to change, and once managements have decided how they are going to do that, they need to explain their strategy to their staff and win them over. Then they need to make sure they are making the most of the talent at their disposal. That news sub might be the world's expert on a certain genre of music or local archaeology or have a quirky writing style that would benefit the paper. Just because he spends his days with his head down correcting reporters' grammar or spelling doesn't mean that's all he knows or all he is fit for. It seems to me extraordinary the way newspapers cavalierly discard people with much to offer solely on the basis of the chair they happen to be sitting in when the cuts come.

Montgomery is telling us that it is impractical to continue with a system where half a dozen or more people handle a story from its inception to its appearance in print or online. He says we have to trust senior people to publish their own copy and, by extension, that means making sure that the people we hire are trustworthy. He is acknowledging that, for subs in particular, a lot of the work is drudgery and that is what he says he wants to remove. If reporters know that the words that appear under their byline are going to be their words and not a version checked and polished by someone else, they might take more care over their stories and do their own name checks.

But Montgomery is going further than this. He wants to see a 20-fold increase in the material produced by his titles. That can be achieved only with radical reorganisation, so this is where the 'harvesting of content' comes in. Essentially he is talking about crowd sourcing - getting the customers to produce the content for nothing and then selling it back to them. Smart business model, eh? There will still be journalists out in the field getting what we would consider 'real' news stories, but those in the office will be marshalling material that he expects to pour in from all quarters.

Steve Auckland, Local World's chief executive, explained to Press Gazette: 'What we want is a 20-fold increase in content on our sites. We can't do it by increasing the number of editorial staff, what we have to do is get lots more user-generated content. So our sports reporter will report on the game and provide analysis and comment, but there will be lots more content coming in from what the fans think about it. So journalists will be curating as well as supplementing that with their own comment.'

Another bit of digispeak there - curating. It's probably the most appropriate word in the new language if you think of an art gallery or museum working out how to present many different pieces so that the visitor can make sense of them.

The entire structure and hierarchy has to change, and once managements have decided how they are going to do that, they need to explain their strategy to their staff and win them over. Then they need to make sure they are making the most of the talent at their disposal. That news sub might be the world's expert on a certain genre of music or local archaeology or have a quirky writing style that would benefit the paper. Just because he spends his days with his head down correcting reporters' grammar or spelling doesn't mean that's all he knows or all he is fit for. It seems to me extraordinary the way newspapers cavalierly discard people with much to offer solely on the basis of the chair they happen to be sitting in when the cuts come.

Montgomery is telling us that it is impractical to continue with a system where half a dozen or more people handle a story from its inception to its appearance in print or online. He says we have to trust senior people to publish their own copy and, by extension, that means making sure that the people we hire are trustworthy. He is acknowledging that, for subs in particular, a lot of the work is drudgery and that is what he says he wants to remove. If reporters know that the words that appear under their byline are going to be their words and not a version checked and polished by someone else, they might take more care over their stories and do their own name checks.

But Montgomery is going further than this. He wants to see a 20-fold increase in the material produced by his titles. That can be achieved only with radical reorganisation, so this is where the 'harvesting of content' comes in. Essentially he is talking about crowd sourcing - getting the customers to produce the content for nothing and then selling it back to them. Smart business model, eh? There will still be journalists out in the field getting what we would consider 'real' news stories, but those in the office will be marshalling material that he expects to pour in from all quarters.

Steve Auckland, Local World's chief executive, explained to Press Gazette: 'What we want is a 20-fold increase in content on our sites. We can't do it by increasing the number of editorial staff, what we have to do is get lots more user-generated content. So our sports reporter will report on the game and provide analysis and comment, but there will be lots more content coming in from what the fans think about it. So journalists will be curating as well as supplementing that with their own comment.'

Another bit of digispeak there - curating. It's probably the most appropriate word in the new language if you think of an art gallery or museum working out how to present many different pieces so that the visitor can make sense of them.

Other groups are already on the same path. Jo Kelly, Trinity Mirror's regionals communities editor, explained her strategy at the News Rewired digital journalism conference last month. And just to prove there's nothing new under the sun, it turns out to be a reheat of the old bonny baby competition; think microwave rather than a covered plate on top of a steaming saucepan.

Readers are encouraged to submit themed photographs, such as snowmen or garden gnomes, to fill in forms nominating the best mum in the world or the most outstanding teacher, to contribute specialist columns, to indulge in a bit of nostalgia and to tweet or share their thoughts about the paper on Facebook.

Kelly displayed examples of how such an approach had filled whole pages - indeed eight pages of pets dressed up as Father Christmas. It may well do, but whether this is quality 'content' that anyone beyond the people taking part would want to buy is a matter of opinion. A more positive aspect was the development and involvement in local campaigns that mattered, such as one that invited mothers to send in pictures of their newborns as part of a fight to keep a baby unit open. But even that isn't new; local papers have always been at the centre of such issues.

Montgomery says he has been inspired by the recent revitalisation of Norway's local media and their sense of community. In an interview for InPublishing, he told Ray Snoddy that he had been dismayed that one of the dailies now owned by Local World did not seem to reflect the character of the distinctive city it served. 'If you look at the Norwegian online sites you will be able to smell the salt air - the characteristic community is built around fishing tradition or farming or technology. You sense there is a community there and the old news agenda dictated by news editors the length and breadth of newspapers is not relevant any more.'

Fair enough. Lots of people are talking about the need to be hyper-local. The problem is, they don't seem to be putting that into practice, especially when papers are being swallowed up by groups that get ever bigger and farther removed from the communities they are serving. How this tallies with the hyper-local ideal is hard to see.

Readers are encouraged to submit themed photographs, such as snowmen or garden gnomes, to fill in forms nominating the best mum in the world or the most outstanding teacher, to contribute specialist columns, to indulge in a bit of nostalgia and to tweet or share their thoughts about the paper on Facebook.

Kelly displayed examples of how such an approach had filled whole pages - indeed eight pages of pets dressed up as Father Christmas. It may well do, but whether this is quality 'content' that anyone beyond the people taking part would want to buy is a matter of opinion. A more positive aspect was the development and involvement in local campaigns that mattered, such as one that invited mothers to send in pictures of their newborns as part of a fight to keep a baby unit open. But even that isn't new; local papers have always been at the centre of such issues.

Montgomery says he has been inspired by the recent revitalisation of Norway's local media and their sense of community. In an interview for InPublishing, he told Ray Snoddy that he had been dismayed that one of the dailies now owned by Local World did not seem to reflect the character of the distinctive city it served. 'If you look at the Norwegian online sites you will be able to smell the salt air - the characteristic community is built around fishing tradition or farming or technology. You sense there is a community there and the old news agenda dictated by news editors the length and breadth of newspapers is not relevant any more.'

Fair enough. Lots of people are talking about the need to be hyper-local. The problem is, they don't seem to be putting that into practice, especially when papers are being swallowed up by groups that get ever bigger and farther removed from the communities they are serving. How this tallies with the hyper-local ideal is hard to see.

Newsquest, Johnston Press and others have introduced templated websites and newspaper designs. So much for individuality. In a way it's rather like our high streets (they all have M&S, New Look, Vodafone, Greggs, but you're served by someone with a different dialect depending on where you live), but of course they are dying too.

Now Local World is treading the same path. A transformation team has been set up (yes, more jargon) and Auckland will be monitoring the activities of the papers on screens from London. The Derby Telegraph, Cambridge News and Exeter Express and Echo were in the vanguard of the operation and others have started moving to new websites. They are identical in appearance - though not, obviously, in content. It isn't encouraging. Particularly when there is an advertisement slap bang over the big picture that leads the site.

There's nothing wrong with asking readers to contribute to your output. Readers used to fill in wedding and obituary forms when I was a junior 40 years ago, the difference now seems to be that there will be no one to rewrite the amateur's efforts. Stringers would file the village news, but again no one will have time to see if there are real stories buried in the WI raffle reports.

As for a sense of community, think who would be the first to dash to the laptop if a site were set up in Ambridge. Does Lynda Snell really represent that community? It is hard to get people involved these days. Guides, Scouts, village hall committees, parish councils, youth clubs and over-60s clubs are all perpetually appealing for volunteers to help them to keep going. The result is that it always seems to be the same people who run the show. There is a danger that an activist minority will end up with the loudest voice - and that may not result in a paper or website that people will want to read. I hope I'm wrong.

Now Local World is treading the same path. A transformation team has been set up (yes, more jargon) and Auckland will be monitoring the activities of the papers on screens from London. The Derby Telegraph, Cambridge News and Exeter Express and Echo were in the vanguard of the operation and others have started moving to new websites. They are identical in appearance - though not, obviously, in content. It isn't encouraging. Particularly when there is an advertisement slap bang over the big picture that leads the site.

There's nothing wrong with asking readers to contribute to your output. Readers used to fill in wedding and obituary forms when I was a junior 40 years ago, the difference now seems to be that there will be no one to rewrite the amateur's efforts. Stringers would file the village news, but again no one will have time to see if there are real stories buried in the WI raffle reports.

As for a sense of community, think who would be the first to dash to the laptop if a site were set up in Ambridge. Does Lynda Snell really represent that community? It is hard to get people involved these days. Guides, Scouts, village hall committees, parish councils, youth clubs and over-60s clubs are all perpetually appealing for volunteers to help them to keep going. The result is that it always seems to be the same people who run the show. There is a danger that an activist minority will end up with the loudest voice - and that may not result in a paper or website that people will want to read. I hope I'm wrong.

Independent web publishers are already getting in under the radar. The News Rewired conference heard from two entrepreneurs who were challenging local papers which they felt were not doing their job properly. Stuart Goulden, founder of One&Other in York, proudly told the session that he didn't employ journalists 'because we're storytellers'. I've no idea what he meant, but his formula is successful - if you measure success in financial terms. His website is attractive and easy to navigate. Pushing the news button brings up teasers for stories about a beer festival, a theatre usher who has worked at the same place for 40 years, and plans for a national cycle race in the city. The most recent appears to be from April 25.

Another speaker was James Fyrne, who runs the SoGlos site. This again is attractive and definitely focused on culture, offering guides to upcoming events, films, gigs and shows, as well as reviews of hotels, restaurants and pubs. Fyrne does employ trained journalists, but not all the writing is brilliant. He has, however, grasped the importance of finding a niche and serving it.

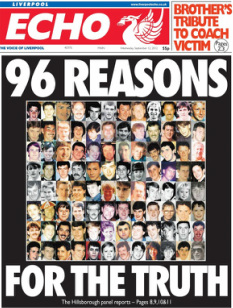

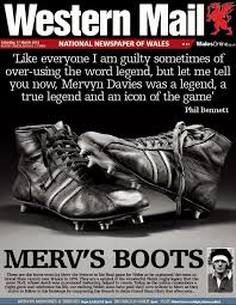

What is sobering is that all this is happening in what should be a period of celebration for our traditional regional papers.

Last week was the Newspaper Society's Local Newspaper Week, with press freedom the central theme. It started with publication of a survey that concluded that about half of regional paper editors thought the Leveson inquiry had had a negative effect on their relationship with their readers. A number of papers ran features highlighting how they could give impetus to local campaigns or carried leaders on how they shouldn't be tarred with the phone-hacking brush. These are issues of huge importance to society as a whole, but whether they are likely to move the readers of the Basingstoke Gazette is another matter.

The Newspaper Society's website tells us that Britain has 1,100 local papers and 1,600 associated websites. About 300 editors are registered on the society's database and it was those editors who were invited to take part in the online survey. Thirty-seven replied.

The Local Newspaper Week page meanwhile trumpeted the 'high-profile' supporters of the week. There were four: Lorraine Kelly, Boris Johnson, Lord Hunt and Lord Judge. This hardly shouts credibility.

We know that regional proprietors are concerned about the cost if they are required to conform to the Leveson regime, but this was feeble propaganda that is unlikely to have done anyone any good.

Another speaker was James Fyrne, who runs the SoGlos site. This again is attractive and definitely focused on culture, offering guides to upcoming events, films, gigs and shows, as well as reviews of hotels, restaurants and pubs. Fyrne does employ trained journalists, but not all the writing is brilliant. He has, however, grasped the importance of finding a niche and serving it.

What is sobering is that all this is happening in what should be a period of celebration for our traditional regional papers.

Last week was the Newspaper Society's Local Newspaper Week, with press freedom the central theme. It started with publication of a survey that concluded that about half of regional paper editors thought the Leveson inquiry had had a negative effect on their relationship with their readers. A number of papers ran features highlighting how they could give impetus to local campaigns or carried leaders on how they shouldn't be tarred with the phone-hacking brush. These are issues of huge importance to society as a whole, but whether they are likely to move the readers of the Basingstoke Gazette is another matter.

The Newspaper Society's website tells us that Britain has 1,100 local papers and 1,600 associated websites. About 300 editors are registered on the society's database and it was those editors who were invited to take part in the online survey. Thirty-seven replied.

The Local Newspaper Week page meanwhile trumpeted the 'high-profile' supporters of the week. There were four: Lorraine Kelly, Boris Johnson, Lord Hunt and Lord Judge. This hardly shouts credibility.

We know that regional proprietors are concerned about the cost if they are required to conform to the Leveson regime, but this was feeble propaganda that is unlikely to have done anyone any good.

Far more encouraging were the Regional Press Awards, which demonstrated that the campaigning spirit and creative flair still flourish. Let's hope that whatever the future holds for the local press, editors are able to continue to produce papers like these.

Monty's vision spelt out

What he said (in gobbledygook) and what he meant (translated into plain English) Plus That memo in detail and how the ideas are being put into practice |

Ashley Highfield wants his local papers to emulate Mumsnet and create 'themed digital destinations'. Is he mad? Why local newspapers matter

|