Al Jazeera on trial: Peter Greste

Conviction quashed, deportation and a taste of freedom

|

February, 2015 The convictions of the three jailed Al Jazeera English journalists were quashed by an Egyptian appeal court judge who said there was no evidence that they had helped the outlawed Muslim Brotherhood and that there was no investigation of claims that they had given evidence under duress. A new trial was ordered, but Greste was immediately deported, having spent 400 days in custody. He said that his primary job would now be to work for the release and acquittal of his co-defendants Mohamed Fahmy and Baher Mohamed.

|

|

Panorama, the Peabody award and prison blogs

Kate Peyton

Kate Peyton

March 6, 2014 Peter Greste was born in Sydney and moved to Queensland when he was 12. A gap year exchange trip to South Africa raised his interest in travelling, and he has said that he was inspired to become a foreign correspondent after reading a biography of the Australian camerman Neil Davis, who died in a coup in Thailand in 1985.

"He was, without doubt, one of the bravest and yet most cautious of men in this business awash with far too many cowboys and fools," Greste told ABC.

Greste returned from South Africa to study journalism in Brisbane and went on to learn the trade in Victoria, Adelaide and Darwin.

He left Australia in 1991 and has since worked as a freelance for the BBC, Reuters, CNN and WTN.

He was the BBC's Kabul correspondent in 1995 and again after the 9/11 attacks in 2001. From there he travelled across the Middle East, Latin America and Africa - where he is the correspondent for Al-Jazeera.

In 2005 he had just arrived in Mogadishu and was standing beside his producer Kate Peyton when she was shot outside an hotel. She died that day. Six years later he returned to make the prize-winning Panorama documentary Somalia: Land of Anarchy.

"He was, without doubt, one of the bravest and yet most cautious of men in this business awash with far too many cowboys and fools," Greste told ABC.

Greste returned from South Africa to study journalism in Brisbane and went on to learn the trade in Victoria, Adelaide and Darwin.

He left Australia in 1991 and has since worked as a freelance for the BBC, Reuters, CNN and WTN.

He was the BBC's Kabul correspondent in 1995 and again after the 9/11 attacks in 2001. From there he travelled across the Middle East, Latin America and Africa - where he is the correspondent for Al-Jazeera.

In 2005 he had just arrived in Mogadishu and was standing beside his producer Kate Peyton when she was shot outside an hotel. She died that day. Six years later he returned to make the prize-winning Panorama documentary Somalia: Land of Anarchy.

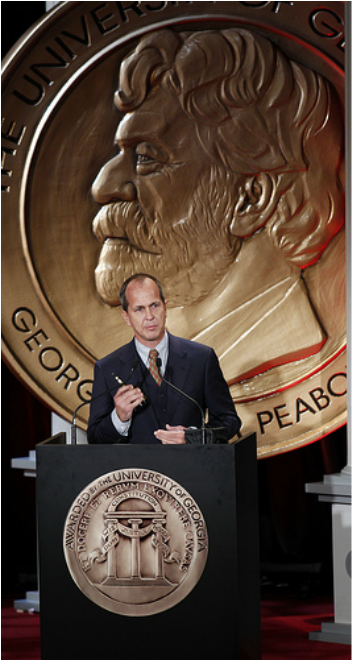

Honoured in America

The Peabody Awards are presented for excellence in any form in any electronic medium - winners have included Jacqueline Kennedy's tour of the White House, and the television programmes Homeland, the Muppet Show and Upstairs Downstairs.

The only criterion is that they should be excellent.

Peter Greste received his in 2011 for the BBC documentary Somalia: Land of Anarchy. The citation said:

The only criterion is that they should be excellent.

Peter Greste received his in 2011 for the BBC documentary Somalia: Land of Anarchy. The citation said:

Six years after his producer was shot dead in Somalia, BBC correspondent Peter Greste returned to the war-ravaged African nation to document everyday life.

What he and cameraman/director Fred Scott report ... is beyond unsettling.

Somalia's misery is encyclopedic: buildings and infrastructure bombed to rubble. Famine. Disease. Refugee camps. Pirates, rebels and religious fanatics vying for control in a never-ending scrum of war.

At great personal risk, Greste and Scott connived to get far afield from the relatively safe enclave in Mogadishu controlled by Somalia's United Nations-backed government.

Through them, we see and hear from UN peacekeeping troops who can't cross a street without risking snipers' bullets, from doctors and burned and maimed Somalians in battered hospitals, and from the shell-shocked noncombatants - the women, children and elderly - who live in unrelenting fear.

The report runs just over 20 minutes, but that's more than enough to make an indelible impression.

The British Foreign Service made the piece mandatory viewing for its Somalia division, most of whose operatives had never experienced the country's crises this up-close.

For its wide-ranging and unflinching portrait of a country eviscerated by years of war, Somalia: Land of Anarchy receives a Peabody Award.

What he and cameraman/director Fred Scott report ... is beyond unsettling.

Somalia's misery is encyclopedic: buildings and infrastructure bombed to rubble. Famine. Disease. Refugee camps. Pirates, rebels and religious fanatics vying for control in a never-ending scrum of war.

At great personal risk, Greste and Scott connived to get far afield from the relatively safe enclave in Mogadishu controlled by Somalia's United Nations-backed government.

Through them, we see and hear from UN peacekeeping troops who can't cross a street without risking snipers' bullets, from doctors and burned and maimed Somalians in battered hospitals, and from the shell-shocked noncombatants - the women, children and elderly - who live in unrelenting fear.

The report runs just over 20 minutes, but that's more than enough to make an indelible impression.

The British Foreign Service made the piece mandatory viewing for its Somalia division, most of whose operatives had never experienced the country's crises this up-close.

For its wide-ranging and unflinching portrait of a country eviscerated by years of war, Somalia: Land of Anarchy receives a Peabody Award.

The Cairo prison blogs

Greste had recently moved from Nairobi to Cairo when he was arrested on December 29. Since then he has written two outspoken blog posts from his cell, in which he has described prison conditions and his concerns for Press freedom.

He starts the first, on January 25, when he was in solitary confinement - the three journalists now share a cell:

"I am nervous as I write this. I am in my cold prison cell after my first official exercise session – four glorious hours in the grass yard behind our block and I don’t want that right to be snatched away.

I’ve been locked in my cell 24 hours a day for the past 10 days, allowed out only for visits to the prosecutor for questioning, so the chance for a walk in the weak winter sunshine is precious.

So too are the books on history, Arabic and fiction that my neighbours have passed to me, and the pad and pen I now write with.

I want to cling to these tiny joys and avoid anything that might move the prison authorities to punitively withdraw them. I want to protect them almost as much as I want my freedom back.

That is why I have sought, until now, to fight my imprisonment quietly from within, to make the authorities understand that this is all a terrible mistake, that I've been caught in the middle of a political struggle that is not my own. But after two weeks in prison it is now clear that this is a dangerous decision. It validates an attack not just on me and my two colleagues but on freedom of speech across Egypt."

He starts the first, on January 25, when he was in solitary confinement - the three journalists now share a cell:

"I am nervous as I write this. I am in my cold prison cell after my first official exercise session – four glorious hours in the grass yard behind our block and I don’t want that right to be snatched away.

I’ve been locked in my cell 24 hours a day for the past 10 days, allowed out only for visits to the prosecutor for questioning, so the chance for a walk in the weak winter sunshine is precious.

So too are the books on history, Arabic and fiction that my neighbours have passed to me, and the pad and pen I now write with.

I want to cling to these tiny joys and avoid anything that might move the prison authorities to punitively withdraw them. I want to protect them almost as much as I want my freedom back.

That is why I have sought, until now, to fight my imprisonment quietly from within, to make the authorities understand that this is all a terrible mistake, that I've been caught in the middle of a political struggle that is not my own. But after two weeks in prison it is now clear that this is a dangerous decision. It validates an attack not just on me and my two colleagues but on freedom of speech across Egypt."

Later in the post he writes:

"I am in Tora prison – a sprawling complex in the south of the city where the authorities routinely violate legally enshrined prisoners' rights, denying visits from lawyers, keeping cells locked for 20 hours a day (and 24 hours on public holidays) and so on. But even that is relatively benign compared to the conditions my colleagues are being held in.

Fahmy and Baher have been accused of being Muslim Brotherhood members, So they are being held in the far more draconian "Scorpion prison" built for convicted terrorists. Fahmy has been denied the hospital treatment he badly needs for a shoulder injury he sustained shortly before our arrest. Both men spend 24 hours a day in their mosquito-infested cells, sleeping on the floor with no books or writing materials to break the soul- destroying tedium. Remember we have not been formally charged, much less convicted of any crime. But this is not just about three Al Jazeera journalists. Our arrest and continued detention sends a clear and unequivocal message to all journalists covering Egypt, both foreign and local.

The state will not tolerate hearing from the Muslim Brotherhood or any other critical voices. The prisons are overflowing with anyone who opposes or challenges the government. Secular activists are sentenced to three years with hard labour for violating protest laws after declining an invitation to openly support the government; campaigners putting up "No" banners ahead of the constitutional referendum are summarily detained.

Anyone, in short, who refuses to applaud the institution. So our arrest is not a mistake, and as a journalist this IS my battle. I can no longer pretend it'll go away by keeping quiet and crossing my fingers. I have no particular fight with the Egyptian government, just as I have no interest in supporting the Muslim Brotherhood or any other group here. But as a journalist I am committed to defending a fundamental freedom of the press that no one in my profession can credibly work without."

"I am in Tora prison – a sprawling complex in the south of the city where the authorities routinely violate legally enshrined prisoners' rights, denying visits from lawyers, keeping cells locked for 20 hours a day (and 24 hours on public holidays) and so on. But even that is relatively benign compared to the conditions my colleagues are being held in.

Fahmy and Baher have been accused of being Muslim Brotherhood members, So they are being held in the far more draconian "Scorpion prison" built for convicted terrorists. Fahmy has been denied the hospital treatment he badly needs for a shoulder injury he sustained shortly before our arrest. Both men spend 24 hours a day in their mosquito-infested cells, sleeping on the floor with no books or writing materials to break the soul- destroying tedium. Remember we have not been formally charged, much less convicted of any crime. But this is not just about three Al Jazeera journalists. Our arrest and continued detention sends a clear and unequivocal message to all journalists covering Egypt, both foreign and local.

The state will not tolerate hearing from the Muslim Brotherhood or any other critical voices. The prisons are overflowing with anyone who opposes or challenges the government. Secular activists are sentenced to three years with hard labour for violating protest laws after declining an invitation to openly support the government; campaigners putting up "No" banners ahead of the constitutional referendum are summarily detained.

Anyone, in short, who refuses to applaud the institution. So our arrest is not a mistake, and as a journalist this IS my battle. I can no longer pretend it'll go away by keeping quiet and crossing my fingers. I have no particular fight with the Egyptian government, just as I have no interest in supporting the Muslim Brotherhood or any other group here. But as a journalist I am committed to defending a fundamental freedom of the press that no one in my profession can credibly work without."

In the second post the next day, Greste writes about the allegations against him and the campaign for his release:

"Journalists are never supposed to become the story. Apart from the print reporter's byline or the broadcaster's sign-off, we are supposed to remain in the background as witnesses to or agents for the news: never as its subject.

That's why I find all the attention following our incarceration all very unsettling. This isn't to suggest I am ungrateful. All of us who were arrested in the interior ministry's sweep of Al Jazeera's staff on December 29 are hugely encouraged by and grateful for the overwhelming show of support from across the globe. From the letter signed by 46 of the region's most respected and influential foreign correspondents calling for our immediate release; to the petition from Australian colleagues; the letter writing and online campaigns and family press conferences - all of it has been both humbling and empowering....

But what is galling is that we are into our fourth week behind bars for what I consider to be some pretty mundane reporting...

This assignment to Cairo had been relatively routine - an opportunity to get to know Egyptian politics a little better. But, with only three weeks on the ground, hardly time to do anything other than tread water. So when a squad of plainclothes agents forced their way into my room, I was at first genuinely confused and later even a little annoyed that it wasn't for some more significant slight.

This is not a trivial point. The fact that we were arrested for what seems to be a set of relatively uncontroversial stories tells us a lot about what counts as "normal" and what is dangerous in post-revolutionary Egypt...

Let me be clear: I have no desire to weaken Egypt nor in any way see it struggle. Nor do I have any interest in supporting any group, the Muslim Brotherhood or otherwise. But then our arrest doesn't seem to be about our work at all. It seems to be about staking out what the government here considers to be normal and acceptable. Anyone who applauds the state is seen as safe and deserving of liberty. Anything else is a threat that needs to be crushed."

"Journalists are never supposed to become the story. Apart from the print reporter's byline or the broadcaster's sign-off, we are supposed to remain in the background as witnesses to or agents for the news: never as its subject.

That's why I find all the attention following our incarceration all very unsettling. This isn't to suggest I am ungrateful. All of us who were arrested in the interior ministry's sweep of Al Jazeera's staff on December 29 are hugely encouraged by and grateful for the overwhelming show of support from across the globe. From the letter signed by 46 of the region's most respected and influential foreign correspondents calling for our immediate release; to the petition from Australian colleagues; the letter writing and online campaigns and family press conferences - all of it has been both humbling and empowering....

But what is galling is that we are into our fourth week behind bars for what I consider to be some pretty mundane reporting...

This assignment to Cairo had been relatively routine - an opportunity to get to know Egyptian politics a little better. But, with only three weeks on the ground, hardly time to do anything other than tread water. So when a squad of plainclothes agents forced their way into my room, I was at first genuinely confused and later even a little annoyed that it wasn't for some more significant slight.

This is not a trivial point. The fact that we were arrested for what seems to be a set of relatively uncontroversial stories tells us a lot about what counts as "normal" and what is dangerous in post-revolutionary Egypt...

Let me be clear: I have no desire to weaken Egypt nor in any way see it struggle. Nor do I have any interest in supporting any group, the Muslim Brotherhood or otherwise. But then our arrest doesn't seem to be about our work at all. It seems to be about staking out what the government here considers to be normal and acceptable. Anyone who applauds the state is seen as safe and deserving of liberty. Anything else is a threat that needs to be crushed."

Please sign up here for SubScribe updates

(no spam, no more than one every week or so)

|

|

|