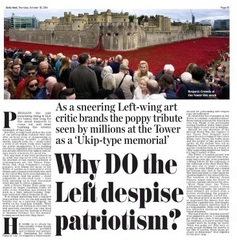

How many were there to remember the fallen, how many wanted to see the spectacle and how many just wanted to know what all the fuss was about is hard to say. What is certain is that a piece of art had captured the public imagination on a scale unseen probably since the Tutankhamun exhibition rolled into London in the 1970s. It had been thought that four million would turn out to take a peek, but that may turn out to be a wild underestimate, given the clamour last week.

SubScribe thought in August that newspapers didn't seem to be taking much of an interest in the project, although they perked up once Wills and Kate turned up.

Then there was some sniffing about where the money from the sale of the poppies at £25 a pop was going. Only a pound a flower for good causes? How dare the artist, his team of workers and those who risked their money to finance the venture take anything for their efforts?

That million quid or so from the poppy sales will have been magnified several times by the raised profile of this year's appeal - especially with the withdrawal from Afghanistan last month. And there will be plenty of commercial enterprises that will have benefited from the installation. I bet the organisers wish they hadn't decided to clear it away so swiftly after its completion in time for Remembrance Sunday next week

Money. Have you noticed how everything ends up being reduced to its monetary value.

We just don't get public art in this country. "Look at that!" we cry. "We could have paid for 12 nurses for a year with that. What a waste of public money!"

Yes, we need nurses. But a dozen more on the national strength won't make much difference to anyone, and what happens next year when the money that would have been saved by not buying the painting or statue or book has gone.

A piece of art lasts forever. Or should.

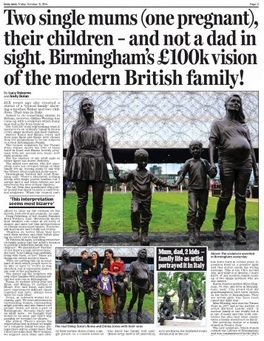

Public art, usually sculpture, lifts the spirit, makes the humdrum more bearable. It's not there for the elite and is as available to the harassed mum with a screaming toddler on one arm and a baby in a pram heading for the shopping centre as it is for the duchess. It is indiscriminate. It is there to be enjoyed by black, brown, white, young, old, fat, thin, married, single, able-bodied or lame. No one can stop you looking. No one can stop you interpreting it in your own way.

But public bodies have to be brave to invest in art. There will always be someone to complain, as the Birmingham MP John Hemming did this week, that councils should instead focus on emptying the dustbins. The Arts Council is always the first to have its budget cut whenever there is a financial squeeze. The whingeing about the licence fee - the "scandal" that we should have to pay a hundred and fifty quid per family for unlimited access to everything the BBC has to offer - is incessant. Particularly from the corporation's rivals.

Well, as SubScribe has written elsewhere, there was no intention to produce an ideal but to portray a "real" family.

The Mail, which was appalled by Gillian Wearing's sculpture, has squealed with delight at the poppies - now that millions have given it their seal of approval. On Friday it devoted a full page, a leader and a diary note to attacking the Wearing work. You could fairly say it was sneering.

SubScribe chooses the word because that is the one it tossed at the Guardian when one of its arts critics dared to suggest that the poppies might be a bit sanitised as a representation of the blood of war. Jonathan Jones actually applauded the fact that people were moved by an artwork, but he took issue with the number of poppies in the installation - one to represent every British serviceman or woman killed during the First World War.

It was, he thought, too inward looking, too nationalistic. What about the millions from other nations? If we wanted peace and reconciliation, why were we concerned only with our own? As a payoff he said that if Cummings had wanted to depict the horror of war, he might have filled the Tower moat with barbed wire and bones.

It was an opinion, an art critic's appraisal of a piece of art. Not all of the piece was antipathetic, but it was the questioning sentences that upset the Mail and prompted a debate into which even the Prime Minister was drawn.

Yes, it was that serious.

The Mail was not alone in this, because by the time Cameron was asked to comment on the Jones view, other papers were talking about "the Left" and "Guardian lefties" wanting the poppies wrenched out out and replaced by barbed wire.

The Mail and Jones are both right - and both wrong. Both pieces of art make a political statement. But both are deserving of their place in our open spaces. Public art matters. The French understand it - look at the "papier mache" sporting figures on the bridges over the road from Calais to Boulogne, whose only purpose is to look nice and raise a smile.

We are rubbish at it. We are too prosaic. We see accurate almost-photographic style representations of everyday objects as good art. We need educating. Bring on more public art in all its forms.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed