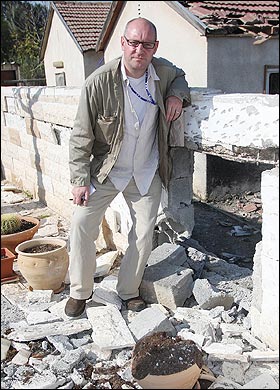

Parkier is the Sun's chief foreign correspondent and in a 26-year career with the paper he has reported from Lockerbie, Iraq, Afghanistan, Bali and Beslan.

He has not, however, worked for 34 months because he has been suspended on police bail since his arrest in February 2012 in the extended aftermath of the phone hacking scandal.

Today he is a convicted criminal, having been found guilty of handling a stolen mobile phone belonging to the Labour MP Siobhan McDonagh. Sentencing him to three months' imprisonment, suspended for a year, Judge Worsley told him: "You were prepared to behave dishonestly in order to get a story...You over-stepped the line between investigate journalism and breaking the law."

This judgment suggests that any journalist offered information in less-than-straightforward circumstances must gamble on whether it is likely to be of public interest without even looking at it.

That is not the same as making a decision on whether to accept the material by balancing its importance against the risk of prosecution.

In 2009, James Harding and Rebekah Brooks were offered tapes detailing every MP's expenses claims. They looked at them, considered the issue of dealing in stolen goods, and turned them down. The material was offered to the Daily Telegraph, which paid £110,000 for it, and we all know the rest of that story.

Harding and Brooks, who knew the tapes were stolen and that they would have to pay to publish them, were guilty of criminally stupid journalistic judgment, but I have never heard anyone suggest that they were guilty of a crime.

Yet they behaved in almost exactly the same way as Parker:

He knew the phone was stolen, he was told that it contained a text about bribery and he agreed to pay Michael Ankers, the student who had turned up with the BlackBerry, £10,000 if the story worked out.

Like Harding and Brooks, he looked at the material, decided against using it, and returned it to the source.

No one would today argue that the publication of MPs' expenses was anything other than in the public interest. Supposing the stolen (or found on the Underground) phone had contained evidence of MPs being involved in bribery. Would that not also have been in the public interest?

Yet today Parker is a criminal for looking to see if that were the case.

This means that journalists will be ever more circumspect about sources and that a whistleblower with important issues to raise may be shown the door if they don't "look right" or because an editor dares not risk checking out what they have to share.

This Government has promised to look after whistleblowers, but the stream of people sacked or hounded out of their jobs for telling the truth flows unabated.

Michael Ankers was not an honourable source trying to right a wrong, but are we to presume that every young man who says he has a story must be a chancer on the make and reject their material without a single, let alone a second, glance?

In an editor's blog for Press Gazette, Dominic Ponsford draws a parallel with the news that Metropolitan Police held on to 1,700 phone records to which they knew they were not entitled for seven months before returning them. It is well worth reading, which you can do here.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed