There are two problems with the rush to condemn the coverage of the Germanwings tragedy. The first is that it stinks of the kind of language-policing that has become all too rife recently. Apparently we must now avoid any word or phrase or expression that might cause offence to any group or individual on Earth, even the newly baptised ‘mental-health issues community’, as if that were really a thing...

And the second problem with this latest round of bash the tabloids (yawn) is that, like so much mental-health campaigning these days, it is obsessed with turning depression into a protected category, something that can never be discussed in a provocative way, almost into an alternative lifestyle which must be accorded respect rather than being stigmatised.

- Brendan O'Neill, Spiked

In less strident terms than Brendan O'Neill, my correspondent said: "It's wrong to say we shouldn't be exploring his depression as background. If someone crashes a plane into a mountain we should consider whether his problems caused him to do that, while, of course, not tarring people with depression as being unfit to work."

Of course it is legitimate to ask questions about motivation. It is not normal to kill 149 people; something strange must have been going on in Lubitz's head. And that something will have been more than a fit of the blues.

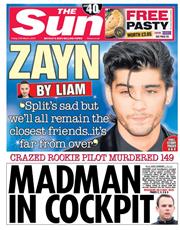

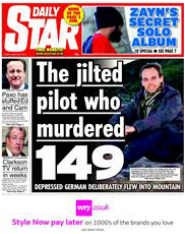

My problem with Friday's papers was the way that "depression" was used as a catch-all term to cover any mental state from melancholy to psychosis and personality disorder.

In a way, O'Neill does that in his column, saying that we should be allowed to call Lubitz "mad", while gibbing at people who describe themselves as depressed when they're really just a bit sad.

There are, however, millions of people who fall into neither category. People who struggle to get out of bed, go to work, look after their families, mix with friends. That is not the sort of "lifestyle choice" most would make. These people don't want to tell their family or friends how they feel or the dark thoughts they harbour - and they certainly wouldn't want their employer to know.

This is where the stigma fears come into play. The self-loathing that comes with severe depression is bad enough, why risk making matters worse by telling the boss, who is bound to regard you as weak, unreliable or unstable?

Once you have "come out" you can never climb back into your closet. Every time you make a mistake or take a day off sick, you will fret that colleagues are whispering about your mental health and suspect that they regard you as weak, as a passenger.

Destroying those preconceptions, among sufferers and among employers, is an incredibly difficult task and that is why the way the media treat mental health and the choice of language is so important.

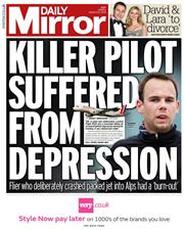

Then consider the Mirror. Simply factual, it seems the less offensive. But to me it suggests that suffering from depression is enough to turn into someone into a mass murderer.

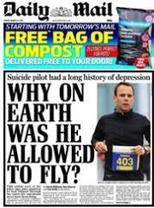

It's obvious that anyone charged with the safety of others should undergo checks that they are fit to do their jobs. Lufthansa said that Lubitz had passed all its tests and was "100% fit to fly". He clearly wasn't.

It is right that we should examine how employers can ensure that their staff aren't putting others in danger. But we also need to take care not to push them into unwarranted intrusions into workers' privacy or to rejecting job candidates on the ground that they once suffered from depression.

Lufthansa was aware of Lubitz's medical history and, under EU rules, should have been monitoring him, both for his own and the passengers' wellbeing. Scrutinising its failings in that regard is a legitimate function of the media.

Implying that depression alone makes you a killer is not.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed